Problems Facing U.S. Disinformation Measures

Kazuki Ichida

(Visiting Researcher, Cyber Security Research Institute, Meiji University)

October 3, 2023

In Japan, countermeasures of the United States against disinformation are considered to be advanced. However, the U.S. is facing a serious problem in implementing such countermeasures. In this paper, countermeasures against information and cognitive warfare from overseas are also included in the term countermeasures against disinformation.

Why Are Fact-Checking and Information Literacy Ineffective?

Before we get to the problems facing U.S. disinformation countermeasures, I would like to provide some background.

There are a certain number of experts who recommend fact-checking and information literacy as effective countermeasures against disinformation or information warfare. For example, much of what is written in Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications’ “MIC’s Approach to Countermeasures against Disinformation” is about improving literacy.[1]

While such countermeasures are indeed necessary, they cannot be considered as sufficient.

Regarding the 2020 U.S. presidential election, for example, some claim that fact-checking and other countermeasures were successful in curbing disinformation and information warfare attacks. However, the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol shows that this was not the case. The ultimate goal of disinformation countermeasures should not be to unveil disinformation and foreign interference, but to reduce their negative effects on society and maintain a healthy information environment. It is clear that the measures taken by the U.S. authorities, platforms, non-profit organizations, and the media have reduced the problems on the surface, but have fallen far short of reducing the negative impact they have on society and achieving a healthy information environment.

Additionally, fact-checking cannot keep up with the scale of disinformation and information warfare. This is because creating disinformation is much quicker and easier than fact-checking.

Trying to increase information literacy can not only be overly burdensome, it also contains the potential for backlash. While seeking information with a high degree of accuracy seems like a good thing, searching through many sources increases the probability of encountering conspiracy theories and the like. Also, nearly all major media outlets have had their share of misinformation and other problems, and seeing information that heavily focuses on such problems can decrease trust in the major media and increase trust in the media that pointed out the problem.

It has also been statistically confirmed that existing major media outlets are biased and risk biasing people’s perceptions more than disinformation.[2] In Japan, biased media reports about the safety of the HPV vaccine have caused problems, including a significant drop in vaccination rates.[3]

Finding reliable information is extremely difficult today. In the process of searching, the risk of falling into the trap of believing false information is much greater.

Also, while many experts focus on interference from abroad, it turns out that interference actually comes more from domestic sources (politicians, political parties, etc.).[4] A focus on the domestic level is also important in terms of protecting democracy. However, in Japan, most of the cases taken up by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications’ “Study Group on Platform Services Final Report” (February 2020) concerned interference from abroad.[5] In addition, the newly established Japanese government organization for combating disinformation also targets interference from abroad.[6]

As will be discussed later, the most important thing in countermeasures against disinformation is to avoid having an information ecosystem in which disinformation spreads domestically, and to avoid increasing the number of people who are prone to believe conspiracy theories, etc. This is also critical from the perspective of national security.

The domestic information environment should be recognized as a priority issue alongside establishing a relationship of trust between the state, the media, and the public, without which appeals for fact-checking and information literacy will be ineffective and sometimes counterproductive.

The attacks against the U.S. disinformation countermeasures exemplify the problems caused by ignoring these basic measures and prioritizing stopgap measures; and similar problems may occur in Japan, which is following the example of the United States.

Attacks from the House Judiciary Committee on Professional Organizations, Experts, and Universities

Currently, there is widespread criticism in the United States of measures taken against disinformation and information warfare. Individual experts, think tanks, and other research institutions are being asked to provide data, are being subpoenaed by Congress, and are being prosecuted. Among those targeted are the Atlantic Council (a think tank that houses the Digital Forensic Research Lab), the University of Washington, Stanford University, New York University, the German Marshall Fund of the United States, the National Civil Rights Conference, the Wikimedia Foundation in San Francisco, and Graphika, a company that investigates online disinformation, all of which are leaders in the field.[7] Particularly targeted were the Election Integrity Partnership, launched by Stanford University and the University of Washington for the 2020 election, and Stanford’s Virality Project, which monitors disinformation about COVID-19. Even volunteer students who worked as interns are being asked to provide information.[8]

The House Judiciary Committee has been playing a central role. There are two major political parties in the United States, the Republicans and the Democrats, and the Republicans have a majority in the U.S. House of Representatives. The Republican Party has a high affinity for conspiracy theories, with some statistics showing that one in four party members are QAnon believers.[9] The Party has also voted that the actions of the group of attackers in the January 6, 2021 assault on the U.S. Capitol were legal. They claim that there is a nexus between researchers and the U.S. government, where conservative speech is being suppressed at the government’s behest, and that tech companies, including social media platforms, have helped in this endeavor.

In some cases, right-wing media, organizations, and critics have sympathized with the attacks on measures taken against disinformation and information warfare, leading to widespread criticism and even lawsuits. The caustic nature of the Republican attack on disinformation countermeasures caused the suspension, after only three weeks of operation, of the National Security Agency’s Disinformation Governance Board (DGB), an advisory body for disinformation measures that was announced on April 27, 2022.[10] The former leader of the DGB has commented that the recurrent backlash against the Board serves to demonstrate the need for this body.[11]

On July 4, 2023, a ruling by Judge Terry Doughty of the U.S. District Court for the District of Louisiana (U.S. District Court) stated that President Biden and authorities had forced social media platform companies to censor their activities, and in order to prevent such “censorship campaigns,” the government and other agencies would be prohibited from contacting social networking platform companies, researchers, and others.[12] Fortunately, the no-contact order was stayed on July 14 under direction of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals.[13] Meanwhile, the Biden administration immediately appealed and the case is still under consideration. The House Judiciary Committee has further expanded its investigative activities by issuing subpoenas to the Attorney General and the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Governments, social networking platforms, and researchers could face the 2024 presidential election without being able to contact each other. In addition, the relevant institutions have been forced to be more cautious in their efforts to combat disinformation. Current attacks on countermeasures against disinformation include even personal attacks, which may force the disclosure of e-mails and other communications with related parties. Considering the bashing of individuals based on the content of such information, it is no wonder that people shy away from researching countermeasures against disinformation.

In addition, Meta and other social networking platform companies have been laying off personnel involved in combating disinformation.[14]

Structural Problems with Disinformation Measures

Since countermeasures against disinformation and information warfare involve issues related to human rights, such as freedom of speech, it is natural and healthy that criticism should be voiced. However, the criticism currently taking place in the U.S. has a strongly partisan tone. At the center of the criticism is the Republican-majority House Judiciary Committee, and the people who filed the lawsuit and issued the ruling on the government’s contact with social networking platform companies and researchers were appointed by Donald Trump when he was president. And many of those sympathetic to this criticism are from so-considered right wing.

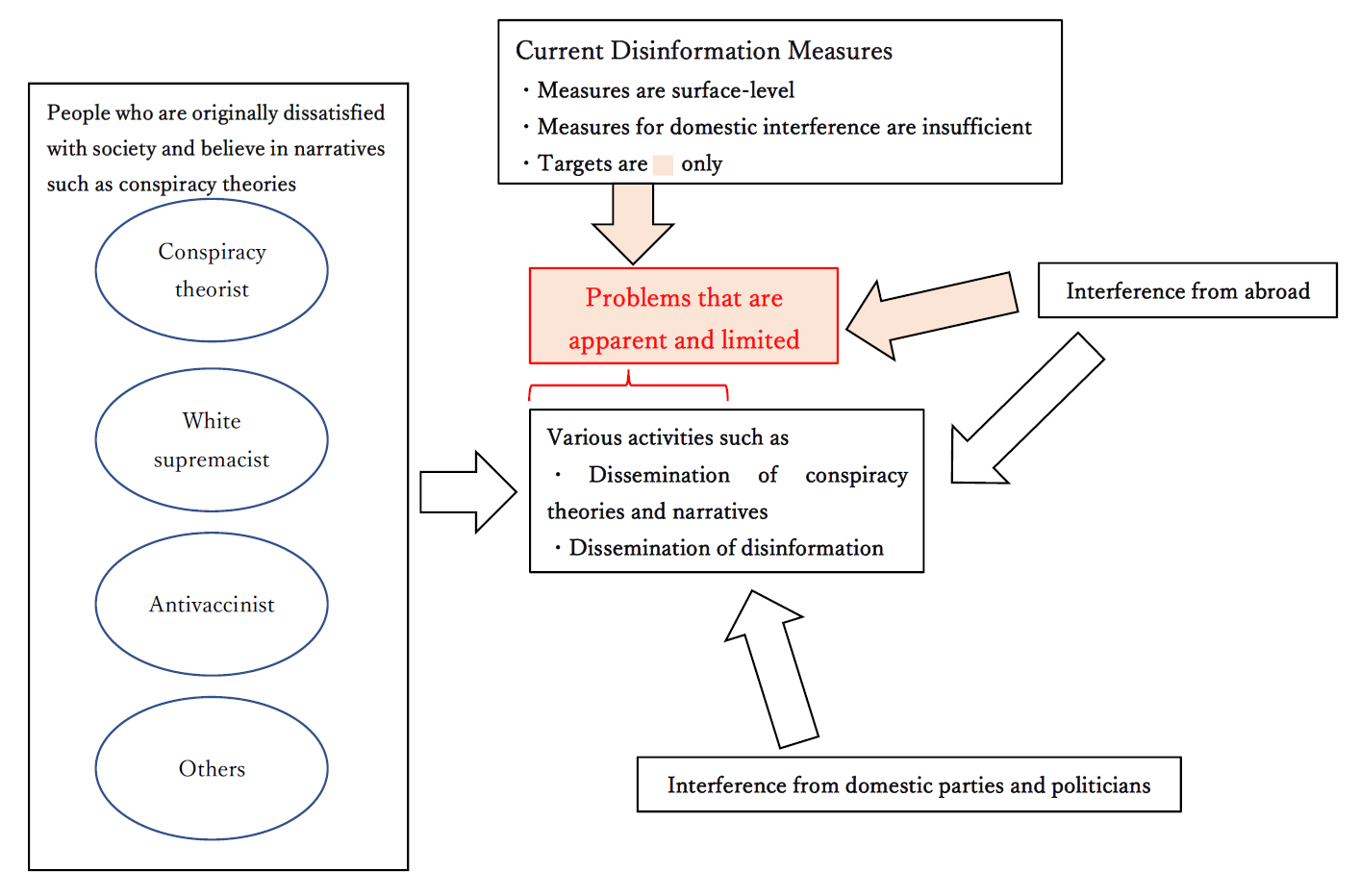

Because many of the people who believe the conspiracy theories and narratives in Figure 1 are Republicans, Republicans are more likely to be critical of disinformation countermeasures.

Figure 1 Ineffective Countermeasures against Disinformation:

Not Much on Interference from Domestic Actors

Source: Prepared by the author

Not only in the United States but in many countries in the Global North, there are growing numbers of people who believe in conspiracy theories and white supremacy, including QAnon. There is also a lot of overlap between these people and anti-vaccine and anti-LGBT activism as well as a pro-Russia stance. Gullibility is easy to understand: it is a form of frustration with the current society that is building up and expressing itself in this way. Denial of the status quo is manifesting in various forms. Thus, it is more natural to think that the activities of those who were originally dissatisfied with society have become more pronounced due to foreign interference, rather than being due to foreign interference in the first place.[15]

In recent years, there has also been an increase in the number of private contractors acting on behalf of disinformation or information warfare operations in various countries, facilitating disinformation operations by domestic and foreign actors.

If domestic movements are not controlled, people can easily be affected by foreign interference. In this regard, domestic movements are far more important than foreign interference. Stopping interference from abroad does not eliminate the activities of conspiracy groups that are originally domestic in nature.

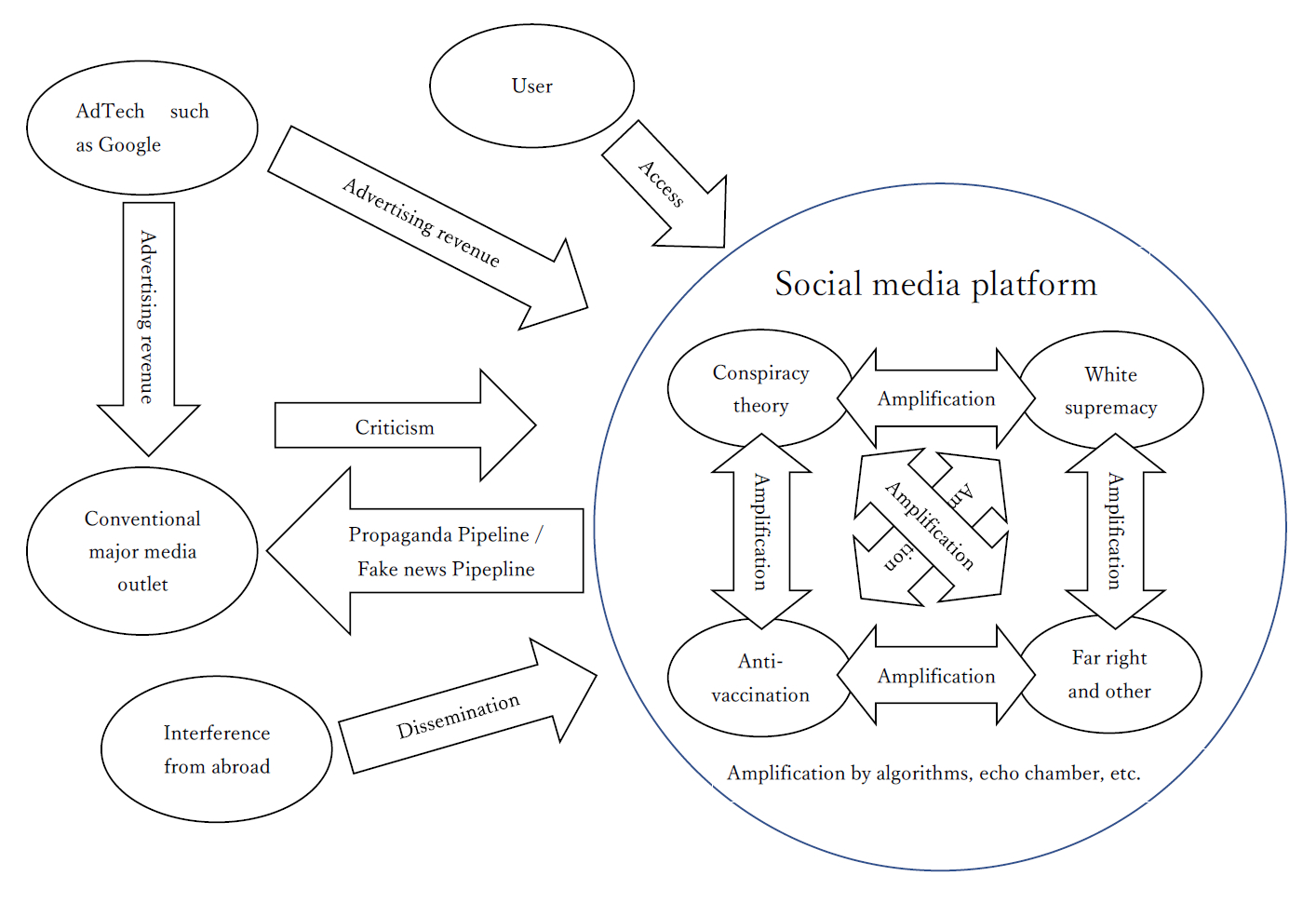

Figure 2 Information Ecosystem that Amplifies Conspiracy Theories and Other Narratives

Source: Prepared by the author

In addition, disinformation and information warfare has become an information ecosystem, as shown in Figure 2, where conspiracy theorists and other believers, ad tech, major media, foreign interference, and social media platforms share mutual benefits. Fact-checking and information literacy do not help solve these structural problems. Currently, fact-checking and information literacy activities are sponsored by ad techs and social media platforms, and there is also the issue of funding sources.

Even if foreign interference is halted, domestic groups bloated in the information ecosystem may continue to operate and expand as they are.

Rather than focusing on superficial events, we must organize the problem structurally and then consider countermeasures, otherwise we will not be able to develop an effective solution.

Conclusion

The current criticism of disinformation countermeasures in the United States threatens to set back the country’s disinformation efforts significantly, and some organizations and researchers have already begun to curtail their activities and reduce their staff. While there is a sound argument for taking measures against disinformation, what is happening is highly partisan and radical behavior by the Republican Party and the right-wing.

Since disinformation is more likely to come from domestic forces than from foreign interference, countering disinformation against domestic forces must be a priority. The U.S. government and research institutions have failed to do so, resulting in attacks from domestic forces. As a result, there is a risk that countermeasures against foreign interference and research may be hindered.

Stopgap measures for individual disinformation are not effective; countermeasures that address the entire information ecosystem are necessary.

【translated by】

Tomohito Nakano (Master’s student, School of International and Public Policy, Hitotsubashi University)

[1]Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, “Gijouyou ni kansuru soumushou no torikumi ni tsuite” (MIC’s Actions on Countermeasures against Disinformation), May 23, 2023. <https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000882504.pdf> [2]Andrew C. Shaver et al., “Media Reporting on International Affairs,” ESOC Working Paper No. 27, 2021. <https://esoc.princeton.edu/WP27> [3]Diego A. Martin, Jacob N. Shapiro, and Julia G. Ilhardt, “Online Political Influence Efforts Dataset (Version 3.0),” Empirical Studies of Conflict Project, February 3, 2022. <https://esoc.princeton.edu/publications/trends-online-influence-efforts> (The page only has a description as of 2020, but if you download the report, it is up-to-date for 2023); Meta, “Recapping Our 2022 Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior Enforcements,” December 15, 2022. <https://about.fb.com/news/2022/12/metas-2022-coordinated-inauthentic-behavior-enforcements/#:~:text=This%20year%20marked%20 20a%20major,our%20public%20reporting%20in%202017>; Samantha Bradshaw, Hannah Bailey, and Philip N. Howard, “Industrialized Disinformation: 2020 Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation,” 2021, Oxford, UK: Programme on Democracy & Technology. <https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/research/posts/industrialized-disinformation/> [4] Kenji Tsuda et al., “Trends of Media Coverage on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in Japanese Newspapers,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 63 No. 12, December 15, 2016, pp. 1634-1638. <https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw647>; Masayuki Sekine et al., “Suspension of Proactive Recommendations for HPV Vaccination Has Led to a Significant Increase in HPV Infection Rates in Young Japanese Women: Real-World Data,” The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, Vol. 16, October 21, 2021. <https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.lanwpc.2021.100300>; Asami Yagi et al., “The Looming Health Hazard: A Wave of HPV-Related Cancers in Japan Is Becoming a Reality Due to the Continued Suspension of the Governmental Recommendation of HPV Vaccine,” The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, Vol. 18, No. 100327, December 13, 2021. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100327> [5]Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, “Purattofōmusābisu ni kansuru kennkyukai saisyu houkokushyo” (Study Group on Platform Services Final Report), February 2020. <https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000668595.pdf> [6]Sankei Shimbun, “Seihu, Gijyouhoutaisaku de shintaisei bunseki・taigaihasshin wo kyouka” (Government, New Structure for Countermeasures against Disinformation: Strengthening Analysis and Outward Dissemination), April 14, 2023. <https://www.sankei.com/article/20230414-VG5SUB5AK5PPPJMG6TQ3F6ZB7Y/> [7]Andrea Bernstein, “Republican Rep. Jim Jordan Issues Sweeping Information Requests to Universities Researching Disinformation ,” Pro Publica, March 22, 2023. <https://www.propublica.org/article/jim-jordan-disinformation-subpoena-universities>; Steven Lee Myers and Sheera Frenkel, “G.O.P. Targets Researchers Who Study Disinformation Ahead of 2024 Election,” New York Times, June 19, 2023. <https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/19/technology/gop-disinformation-researchers-2024-election.html>; Naomi Nix and Joseph Menn, “These Academics Studied Falsehoods Spread by Trump. Now the GOP Wants Answers,” Washington Post, June 6, 2023. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/06/06/disinformation-researchers-congress-jim-jordan/> [8]Steven Lee Myers and Sheera Frenkel, “G.O.P. Targets Researchers Who Study Disinformation Ahead of 2024 Election,” New York Times, June 19, 2023. <https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/19/technology/gop-disinformation-researchers-2024-election.html> [9]PRRI, “The Persistence of QAnon in the Post-Trump Era: An Analysis of Who Believes the Conspiracies,” February 24, 2022. <https://www.prri.org/research/the-persistence-of-qanon-in-the-post-trump-era-an-analysis-of-who-believes-the-conspiracies/> [10]Nicole Sganga, “What Is DHS’ Disinformation Governance Board and Why Is Everyone So Mad about It?” CBC NEWS, May 6, 2022. <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/what-is-dhs-disinformation-governance-board-and-why-is-everyone-so-mad-about-it/> [11]Shannon Bond, “She Joined DHS to Fight Disinformation. She Says She Was Halted by… Disinformation,” NPR, May 21, 2022. <https://www.npr.org/2022/05/21/1100438703/dhs-disinformation-board-nina-jankowicz> [12]Michael Shear and David McCabe, “Ruling Puts Social Media at the Crossroads of Disinformation and Free Speech,” New York Times July 5, 2023. <https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/05/us/politics/social-media-ruling-government.html>; Kevin McGill, Matt O ‘Brien, and Ali Swenson, “Judge’s Order Limits Government Contact With Social Media Operators, Raises Disinformation Questions,” AP, July 5, 2023. <https://apnews.com/article/social-media-protected-speech-lawsuit-in. junction-d8070ef43b3b89e8e76b4569c77446d9>; Darrell M. West, “We Shouldn’t Turn Disinformation into a Constitutional Right,” The Brookings Institution, July 11, 2023. <https://www.brookings.edu/articles/we-shouldnt-turn-disinformation-into-a-constitutional-right/> [13]Cat Zakrzewski, “5th Circuit Pauses Order Restricting Biden Administration’s Tech Contacts,” Washington Post, July 14, 2023. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/07/14/5thcircuit-biden-socialmedia-stay/> ; David McCabe and Steve Lohr, “Social Media Restrictions on Biden Officials Are Paused in Appeal,” New York Times, July 14, 2023. <https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/14/technology/biden-social-media-order.html> [14]Cat Zakrzewski, Naomi Nix, and Joseph Menn, “Social Media Injunction Unravels Plans to Protect 2024 Elections,” Washington Post, July 8, 2023. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/07/08/social-media-injunction-doughty-biden-2024-elections/> [15]Kazuki Ichida, “In’bōron’to roshiano yoron’sōsao sodateta ōbēmin’shushugikokuno kakusa” (Conspiracy Theories and Russian Public Opinion Manipulation Fostered Disparities in Western Democracies), Newsweek Japan, May 10, 2023. <https://www.newsweekjapan.jp/ichida/2023/05/post-46.php>

After managing several IT companies, Kazuki Ichida became a permanent resident of Canada in 2011 and moved to Vancouver. At the same time, he made his debut as a novelist. He has published many novels about cyber crimes that could happen in real life, as well as books and reviews about the manipulation of public opinion on the Internet. In recent years, he has written extensively on digital influence operations.