Are Disengaged Centennials Endangering Democracy?

A technocratic future for decision-making might be brewing within consolidated democracies

Sascha Hannig Núñez

(Master’s student, School of International and Public Policy, Hitotsubashi University)

September 28, 2022

Current world affairs such as the invasion of Ukraine, the spread of Covid-19, human rights, disinformation, or the increasing distrust of people towards democracy, raise uncertainty around the future of liberal societies. While authors such as Larry Diamond have long warned about factors that contribute to the erosion of this system, democratic indexes such as those compiled by Freedom House, The Economist, or Pew Research Center portray a global decrease in commitment towards democracies, especially during the last decade.

Although these trends are generalized in the population, centennials (zoomers or Gen Z), aged 18 to 28, show the most worrisome change, and there is little research on this cohort compared to the millennials. Thus, introducing a picture of their current values will help us understand the impact of today’s international crises in the future. Moreover, even though intuition may indicate that the younger generation is rather homogeneous because of access to information, education “standardization,” and cultural globalization, there might be important – and unmeasured – nuances in perception, participation, or values.

Millennials, centennials, and the problem of generations

Discussing a “young generation” has its own complexity, as it implies that individuals who were born within a set of dates are intrinsically assumed to share attitudes across the world. The current “under 30” voting group is built upon two distinctive cohorts: centennials and millennials.

Following the line of Mannheim’s theory presented as “the problem of generations,” millennials have been described as a highly educated generation with poor economic opportunities, which causes frustration. Millennials were heavily impacted by the gap of expectations caused by the 2008 crisis, which shaped their life choices and frustrations towards the system. Millennials are, therefore, more critical of the political system and, depending on the country, tend to be more revisionist towards institutions.

On the other hand, centennials were young enough to adapt to the new conditions of the after-crisis world, creating set of behavioral particularities. For example, in some countries they are even less engaged with politics or democracy, and in others they seem to be more technocratic. Moreover, this group’s opinions towards governance have been impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic and the events surrounding it. This could translate, for example, in their views on the role of science in policy making, or the impact of disinformation in a population in times of crises.

These differences are currently measurable in some countries. For example, a survey by Genron NPO, a Japanese think tank, found that most Japanese people don’t trust democracy, with only 17% of “trust” across the 30–39 age cohort. By contrast, younger citizens showed more commitment, reaching 36% in those aged 18–20, and 25.5% among those in their 20s.

Exposure to the internet and digitalized debate has also been addressed as a cultural trait of younger generations, which is said to homologize values across borders. The relation between time spent on the internet and behavior was addressed by N. Swigger (2013), who proposed that “technology may be altering American attitudes on basic democratic values.” Therefore, there is an arguable relation between information access, political participation, and democratic culture, as well as an interaction – and shift – on democracies in the long term, depending on the society in question.

Centennials less committed to democracy in developed countries, while new democracies might hold the key to engaging youth

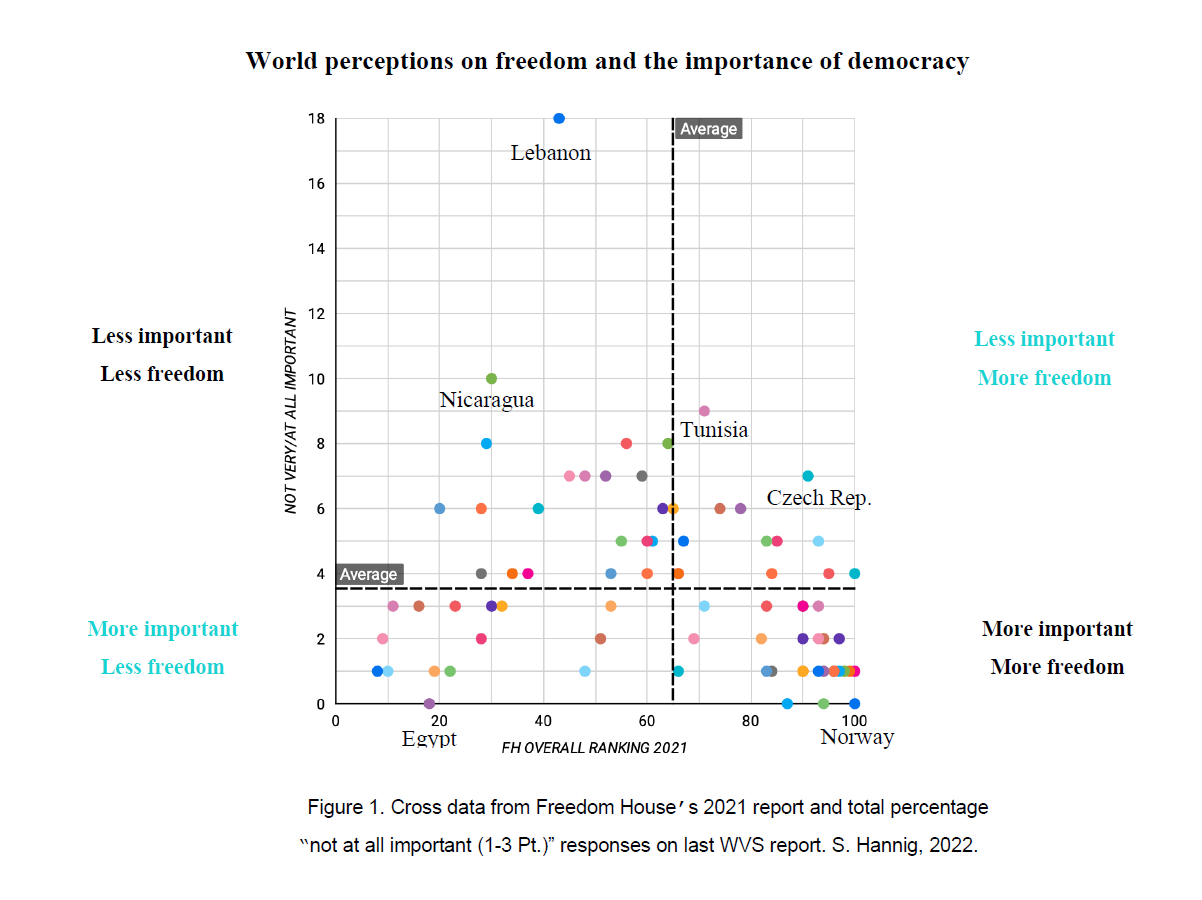

A static picture of the attitudes of people aged under 29 from the World Values Survey (WVS) gives us a better understanding on how this generation relates to democracy. The sample was selected by crossing the surveyed countries with the 38 that are considered “free” in Freedom House’s 2021 annual report.

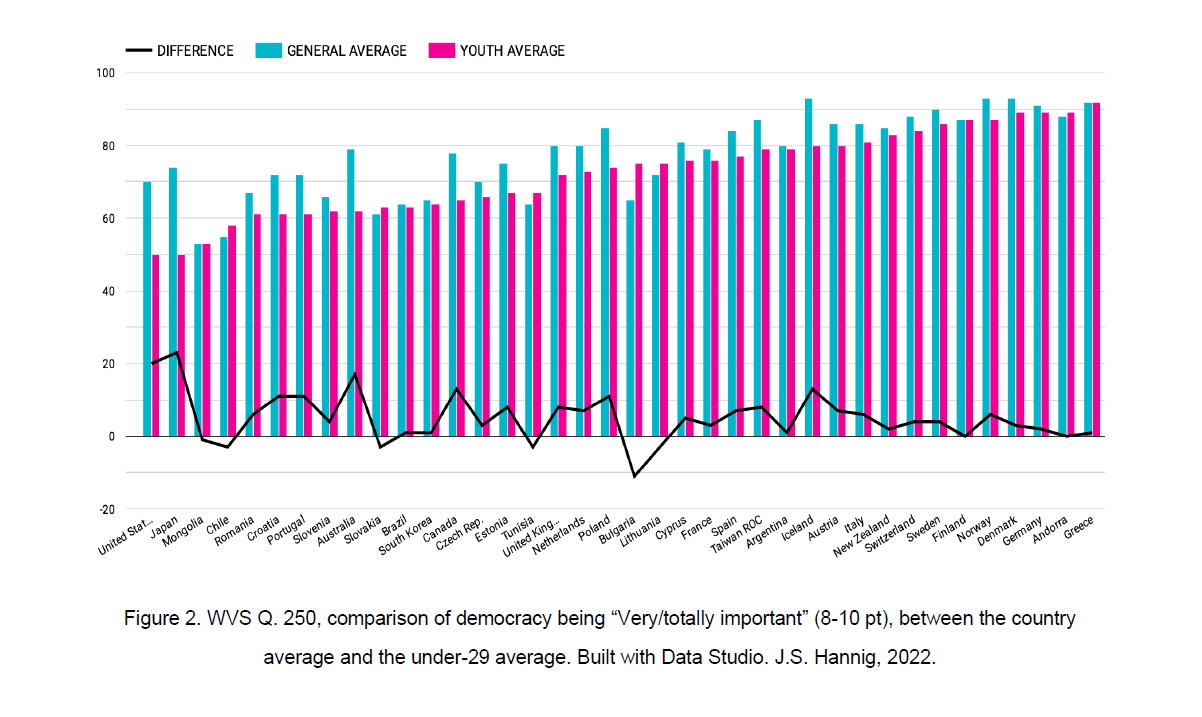

The first analyzed item is “importance of democracy,” which is often cited as the most important question to measure populations’ support for this system. Figure 1 shows that few people, even in authoritarian countries, state that “democracy is not important.” Nevertheless, when comparing averages of “importance of democracy” with the “under-29” cohort (Figure 2), relevant differences come to light. First, while most younger citizens had a lower esteem for democracy than the average, there are outliers such as Tunisia, Mongolia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Chile, and most dramatically Bulgaria, with the under-29 cohort having a +10% increase. Interestingly, Greece has the highest esteem for democracy among younger people, in spite of not being among the highest ranked countries in the report.

On the other hand, some consolidated democracies showed large decreases. Regarding Japan, the analysis confirmed what is shown in Gen NPO’s survey mentioned above, with 21% of respondents answering “I don’t know” instead of choosing a lower level of importance, which led to a net decrease of more than 23%. In the Gen NPO, the youngest cohorts exhibited less resolution to commit, with more that 30% answering “don’t know” when asked about their trust in democracy. The US, one of the most concerning cases analyzed globally, goes down by almost the same amount, with more than 19%, evidencing a disengaged youth in which 20% leaned towards “neutrality.”

A more technocratic youth across democracies may lead to support for “wise” expert decision making but also an autocratic path

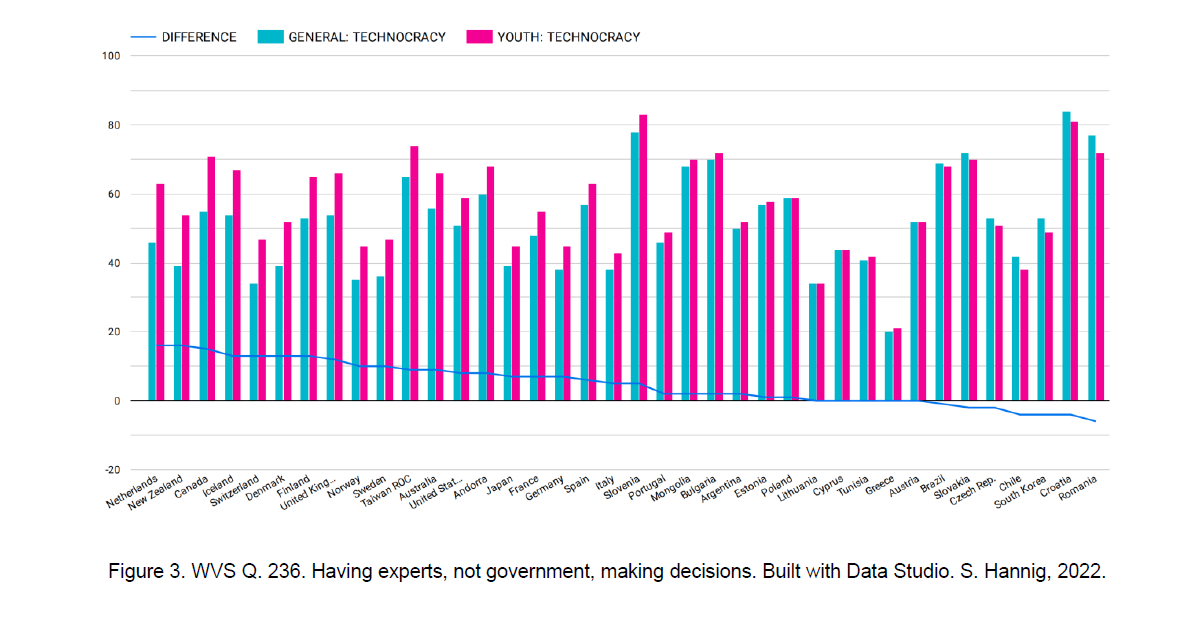

In a 2019 study about democratic values, Fondation pour l’innovation politique found that 48% of younger citizens (under 35 years old) supported a vote system limited by a citizen’s education level. This is not new, as youth backing for filters in decision-making mechanisms has been detected by other studies. These trends indicate that younger voters may pursue a rather technocratic or epistocratic approach to decision-making. This analysis (Figure 3) shows that the under-29 cohort tend to be more supportive of professional decision-making than average voters, and the largest gaps appear in more consolidated western democracies, such as the Netherlands, New Zealand, or Canada, indicating that young people in these countries are more likely to stay disengaged with traditional institutions compared with their predecessors, and look for experts to make decisions rather than elected leaders.

What causes this rejection of politicians’ capacity? One possibility is that, in an era of highly polarized societies, decision-making is sometimes to be grounded on political interpretations of reality (and ideological struggles) rather than facts themselves. On top of that, disinformation and fake news inject more uncertainty into facts and reality, which might influence a generation that is highly aware of these methods of deception and how some politicians have fallen into using them. The recent experiences of Covid-19 pandemic policy might provide an example of this. Some societies were flooded with fake news and provided unscientific responses, while other governments abused their power by taking advantage of the health emergency or interpreting only one aspect of reality.

On the other end of the spectrum, Greece’s youth indicated the lowest support for this kind of practice, while Slovenia ranks close behind and Romania has the largest difference in technocratic support compared to the average. This does not mean that these young citizens trust their current government more, but they think technocrats should have less power. In authoritarianism, technocrats are sometimes used as “shields” to justify unilateral actions by the government – take as an example industrialism in the Soviet Union – and newly formed democracies know about this better than consolidated ones.

Antisocial behavior is more important to predict future outcomes than stated support for democracy

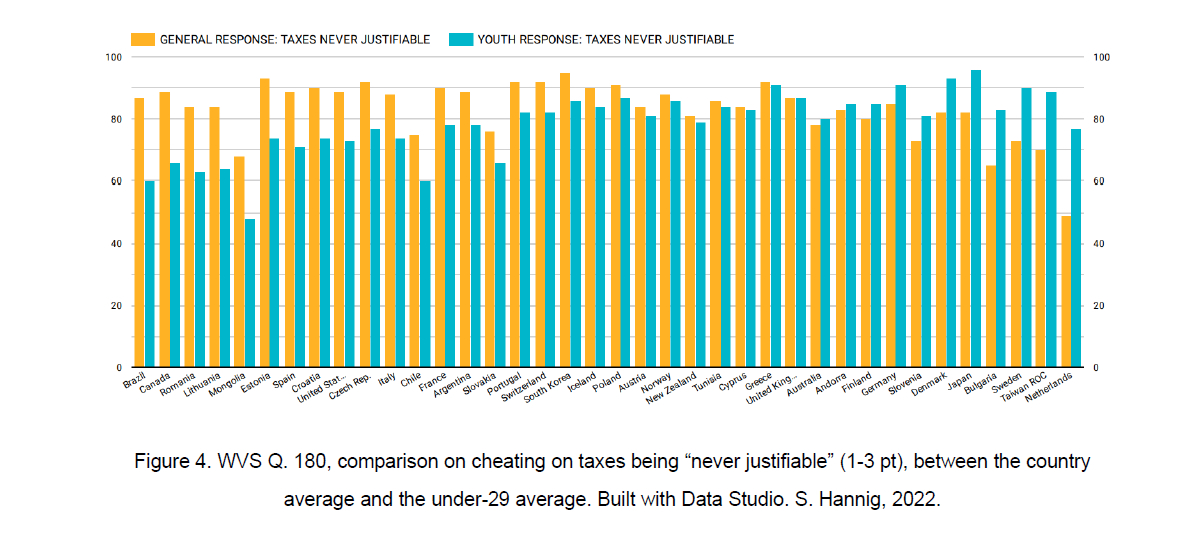

Previous studies use WVS data to elaborate on younger generations’ democratic attitudes. Foa and Mounk proposed that citizens in Western democracies have “become more cynical about the value of democracy as a political system,” emphasizing millennials’ attitudes, whereas Voeten concluded that general attitudes towards democracies are “flat” if compared with the historical data, because younger people have always tended to be more critical of democracy. Meanwhile, diverting traits appear within other regions. A 2016 study in Latin America showed that more than two thirds of school students would support a dictatorship if it brought economic benefits or security. Howe (2017) warned about the worrisome changes in US attitudes towards democracy, and targeted antisocial behavior, such as supporting tax evasion or bribery in their societies, as a key factor in erosion.

Not all centennials support cheating

When analyzing the issue of “cheating on taxes” (Figure 4), one of the first things that stands out is the gap between some countries. The younger generation in the Netherlands, Taiwan, Japan, or Sweden strongly reject this practice when comparing with the average, while youth in countries like Brazil, Canada, Estonia, or Mongolia tend to overlook it. These results make it very difficult to find a trend among democracies and indicate that recommendations should be targeted towards groups of countries that follow the same behaviors.

Canada’s youth keener to tolerate political violence

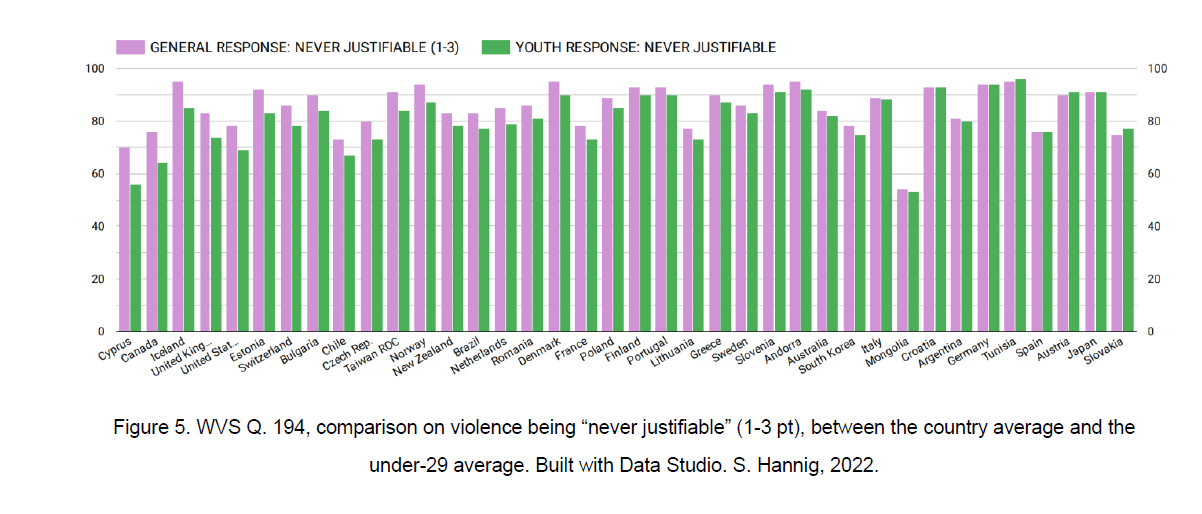

Another antisocial behavior is political violence (Figure 5). Again, Canadian young citizens have one of the largest gaps after Cyprus, which warns about the dramatic change in generational attitudes. Overall, younger citizens were “more violent” than the average, but this is not an absolute trend, with cases like Slovakia, Japan, Austria, and again Tunisia, where the youth strongly condemn violence.

Recommendations

The opinions of young people – as is the case with any social, ethnical, or generational group in the world – are nuanced and not monolithic. For example, countries like Japan exhibited a relevant gap in “democratic support,” and yet, their younger population doesn’t support antisocial behavior. With this in mind, recommendations may be divided into categories, such as the level of commitment to democracy or the most concerning anti-democratic attitudes.

First, stronger support for technocrats can be used as a strength. A country whose youth prefer that policies be constructed by experts and not politicians does not necessarily exhibit weak democratic values. Nevertheless, it might indicate a lack of trust in conventional democratic decision-making and support for more totalitarian and elitist forms of government. In this case, it is relevant to investigate in future research whether the younger cohorts of these populations also have antisocial behavior.

With that in mind, considering the dramatic changes in governance that some societies undertook during the Covid-19 pandemic in terms of considering “science” in policy making, it might be worth channeling this preference for expert participation, perhaps by considering and publicizing specialized arguments and figures in the decision-making process, to enhance the trust of this new generation towards an efficient and fact-based democracy.

Second, consolidated democracies with antisocial youth must urgently be re-engaged with values. Countries like Canada or the United States should be closely surveyed and a solid long-term strategy should be addressed to counter the current trend. Policies that seek to engage with these young populations should also look for the consolidation of democratic values. Moreover, there is an urgent need for awareness among policy makers around the issue of civil and political culture, as way as to invite initiatives that promote democratic values around young people’s environment. Social media should also be evaluated as a vector and, when possible, used as a channel to spread these concerns. In other words, it is necessary to find ways to institutionalize these young people’s concerns about democracy, so they don’t resort to extra-official or antisocial means that might end up eroding democracy rather than saving it.

Third, younger democracies with young democrats can be an asset for democratic consolidation. Countries that do not rank the highest in Freedom House’s report, such as Greece, Bulgaria or Tunisia, but show a youth that is more engaged in democracy than the country average, provide a great opportunity to improve the country’s future development. Providing tools to the new generation to expand the support for liberal democracies internally and through the international community may help to counter illiberal trends that have endangered the future of democracies. Moreover, generating networks with these key populations will also help to understand the differences that make these countries’ centennials more engaged with democratic governance than the average population.

To conclude this stream of thought, even though young generations differ across countries and even within societies, there are circumstantial elements that can be addressed by policy makers to strengthen future leadership and societies that will grow into consolidating democracies around the world. In particular, policy makers can look for common traits such as the relation between technology and the different international threats posed by illiberal movements.

Sascha Hannig Núñez is a Chilean analyst of international relations, with experience as a financial reporter. She currently consults for several organizations, collaborates as an associate researcher at the Instituto Desafíos de la Democracia, and supports the Institute for Global Governance Research at Hitotsubashi University, Japan, as an assistant. Her main fields of study are China’s global influence and the implications of science and technology in society. Hannig has a master’s degree from the Adolfo Ibáñez University and is pursuing a master’s degree in Global Governance at Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo as a JICA scholarship student for the SDG Global Leaders program. In addition to her academic interests, she is a fiction novelist with five novels and works published in three languages and has co-hosted the En el Fin del Mundo podcast.