Humanitarian Assistance to Myanmar: Assessing Aid Delivery in Conflict Zones

Masao Imamura

(Professor, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Yamagata University)

February 2, 2024

Does humanitarian assistance from a faraway country like Japan actually reach people in need of international aid in Myanmar? Those who donate to a humanitarian cause will naturally want to know if their donation actually reaches and helps the target population, while those hesitant to donate may have doubts about whether their good will actually makes a difference. In general, it is extremely difficult to examine and verify “what, when, where, how, by whom, and to whom” of aid delivery in the case of humanitarian crises like the one unfolding in Myanmar today because it is not easy to track humanitarian goods and services in conflict zones. This contrasts with the recent push for the “traceability” of commodities, especially agricultural products, from the production stage to final consumption and/or disposal. Given the difficulty of achieving aid traceability, how can we assess humanitarian delivery?

Access to conflict areas in Myanmar is so severely restricted by Myanmar’s junta that it is in practice impossible for agencies like the United Nations (UN) to operate a humanitarian program independently of the military government. Official UN humanitarian assistance activity in the country is in fact concentrated in particular cities and displaced persons camps; more than 80% of the food aid in the UN Humanitarian Response Plan for 2023 was provided in two places: Yangon (the largest city) and Rakhine State (where large camps for Rohingya are located).[1] About these official aid programs, recognized and sanctioned by the military government, we are able to find some information in the public domain. In contrast, however, we know little about humanitarian assistance in conflict areas. Even when humanitarian projects in conflict zones is negotiated behind the closed door, the details remain inaccessible to the public.

While local grassroots organizations are engaged in humanitarian assistance in conflict zones, these small groups rarely disclose the details of their activities. One reason for this is that, unlike the United Nations and international NGOs, these grassroots organizations may not need to regularly produce detailed reports for donors. Many of them do not have foreign donors, and it is not in their interest to allocate precious resources to writing bureaucratic reports. A more fundamental reason, however, is that these aid projects in conflict zones cannot disclose information that could put the aid workers at risk. In conflict zones across Myanmar, it is often necessary for humanitarian projects to coordinate with local units of Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs).[2] Such relationships may make the humanitarian project a target of junta’s offensives. Attacks on aid workers have been widespread since the coup in Myanmar: in 2021 and 2022, Myanmar’s military attacked humanitarian aid workers at least 39 times. The killing of two local staff members of Save the Children in Kayah State in December 2021 was widely reported. Military attacks on healthcare workers occur even more frequently: as of October 19, 2023, the cumulative number of attacks since the 2021 coup had reached 1,088, resulting in the killing of 107 healthcare workers. More than 170 health and medical facilities have been attacked, including one built with the support of the Japanese government in Magwe District. At least 19 people working at this facility were abducted in a violent raid in April 2023.

The questions to be raised here are: how can we measure the effectiveness of humanitarian aid to conflict zones in Myanmar? Is there a reliable way to collect quantitative data about aid delivery? Recent research by Humanitarian Outcomes (HO), an organization founded in 2009 in the U.K, is helpful in answering these questions. The organization regularly publishes country-specific reports called SCORE (Survey on Coverage, Operational Reach, and Effectiveness). In the past five years alone, SCORE surveys have been conducted in Northern Nigeria, the Central African Republic, Afghanistan, Tigre (Ethiopia), Iraq, Yemen, and Haiti. In April 2023, SCORE released its first ever report on Myanmar.

A noteworthy aspect of HO’s research methodology is the use of mobile phone surveys for data collection,[3] With the incentive of sending coupons to survey respondents, the survey secured a sufficiently high response rate, to reach 90% of confidence level.[4] In the past, such statistical surveys would have been limited to countries with good telecommunications infrastructure, but the global proliferation of mobile phones during the past decade has made it possible to conduct robust surveys in countries like Myanmar. Due to the low literacy rate in some areas, the survey method chosen for Myanmar was to collect data through individual telephone interviews with each respondent rather than text responses and machine processing.

HO conducted its survey across the country in December 2022 and received a total of 501 responses (250 women and 251 men) from all the fourteen Regions and States. In addition to the random survey results, HO also interviewed about 30 experts to obtain qualitative data to help interpret the quantitative data; this included 21 staff members of international humanitarian organizations and 10 staff members of local organizations working in Myanmar. In principle, HO collects data based on the same questionnaire regardless of the country or region of interest, allowing for comparisons between different countries and regions. All quantitative survey responses (rendered anonymous) are available on the HO website (this is true not only for Myanmar, but also for other SCORE surveys covering other regions). The raw data, therefore, can be used by third parties to conduct their own analysis.

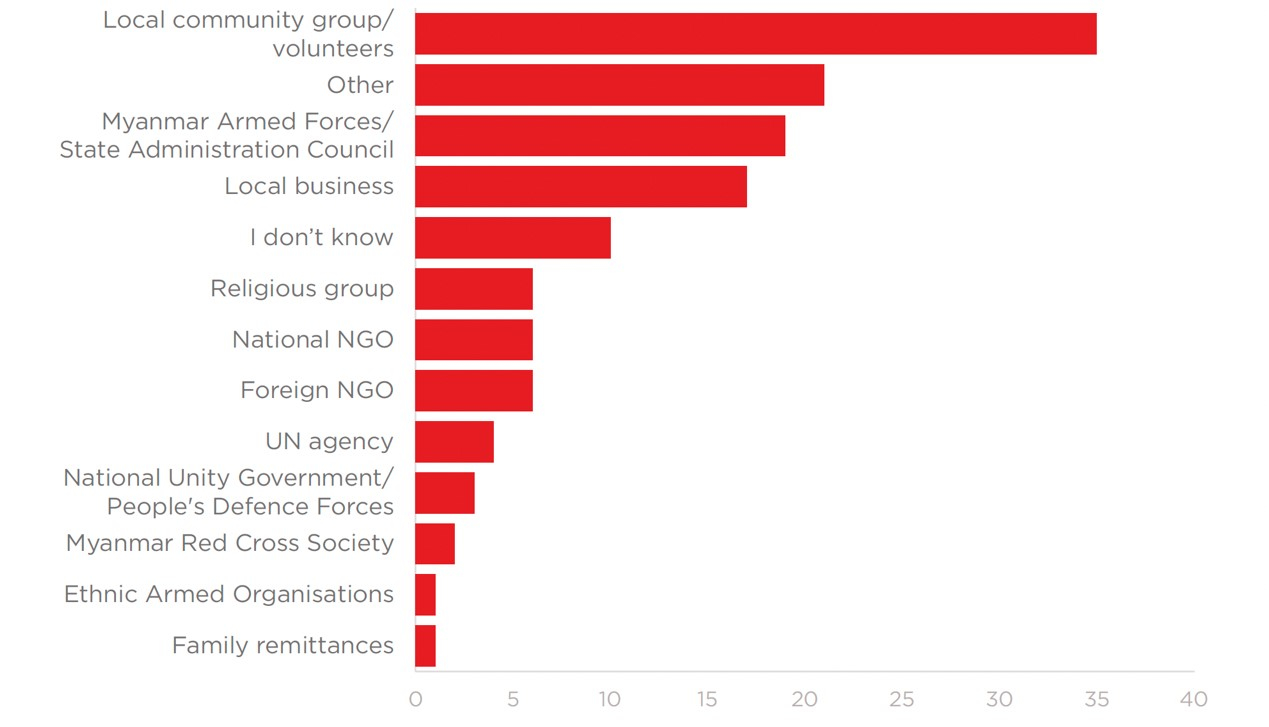

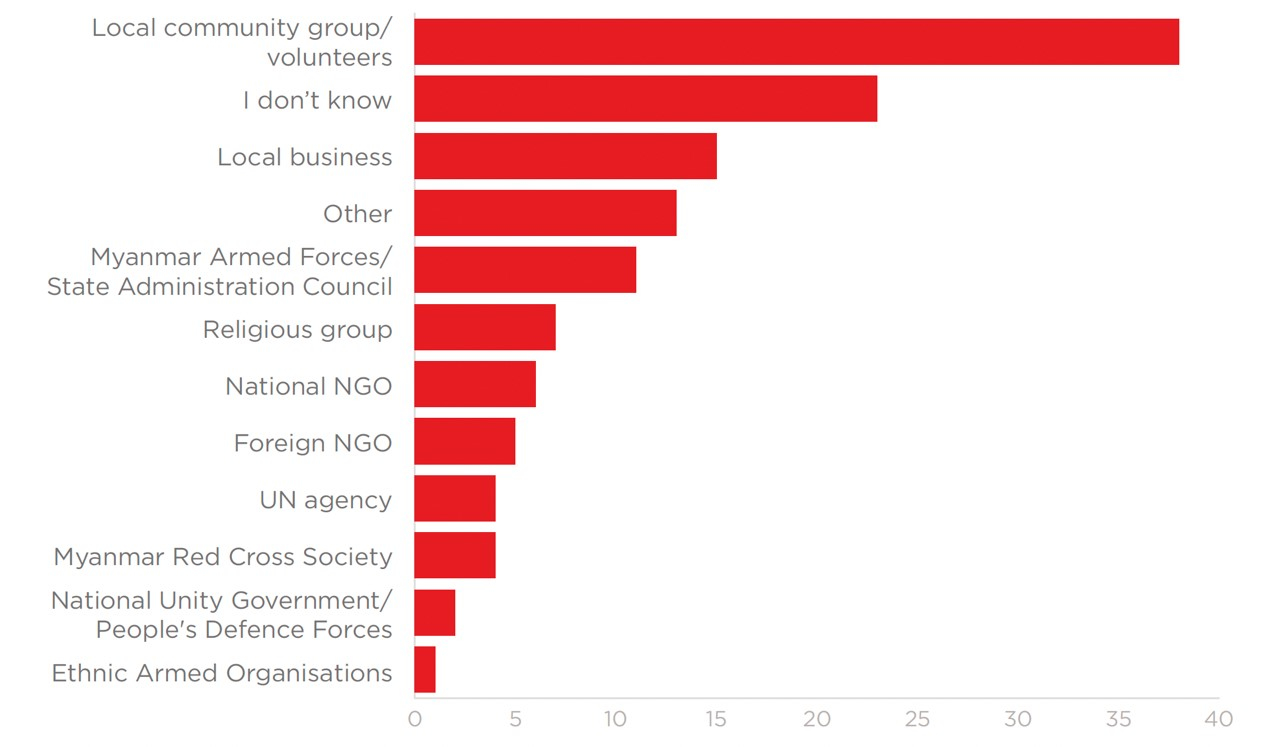

Let us look at some of the notable trends in Myanmar in comparison with other countries by focusing on two questions: “Who provided the aid you received?” (Question 8) and “Which type of aid providers have been best able to reach populations in need in the last year?” (Question 13).[5] The distribution of responses by 501 individuals to these two questions is as follows.[6]

Table 1: “Who provided the aid you or your household received?” (Question 8)

Source: Humanitarian Outcomes, “Humanitarian Access SCORE Report: Myanmar” (April 2023), p.13.

Table 2: ” Which type of aid providers have been best able to reach populations in need in the last year?”(Question 13)

Source: Humanitarian Outcomes, “Humanitarian Access SCORE Report: Myanmar” (April 2023), p.15.

These survey results highlight the vital importance of local actors. We can say that, as far as the recipients’ experiences are concerned, it is most often local community and business groups that deliver food, other goods, and cash to beneficiaries. Myanmar’s strong localism is even more pronounced when compared to other countries such as Tigre (Ethiopia), where the International Red Cross, international NGOs, UN agencies, and the Ethiopian Red Cross were the top aid deliverers. While “local business” is ranked in the fifth place, “local community group/volunteers” is nowhere to be found. In Myanmar, by contrast, the UN and international NGOs do not appear to be major players in aid delivery, according to the survey results. Of course, it may be that these international organizations deliberately keep a low profile by limiting their involvement to behind-the-scenes roles. Indeed, the report mentions that humanitarian aid organizations make efforts to conceal their identities by removing their names and logos when delivering aid. Another notable finding is that cash transfers are more appreciated than goods, as the latter could be more easily found and confiscated en route. In order to cope with military and policy checkpoints, commercial delivery services are often utilized.

The HO report stresses that humanitarian work in Myanmar can be life-threatening: “It is very dangerous. If they [army] find you, they will kill you.”[7] The large number of “I don’t know” responses to the two questions above may also be inferred to reflect the serious risks involved in providing humanitarian assistance in Myanmar. The survey results also show that the contributions from the opposition forces such as EAOs, People’s Defense Force (PDFs), and National Unity Government (NUG) are quite low. It would be difficult, however, to accurately ascertain the level of contributions of these anti-government groups through a telephone survey, since it is unlikely that respondents would truthfully disclose to a stranger that they receive support from actors deemed “terrorist” by the Myanmar military. It is easily conceivable that although the respondent in fact knows the aid donor, they may deliberately choose “I don’t know” in the survey.

To reiterate, two particularly salient findings from the HO report are as follows. Firstly, that formal aid programs deployed by international organizations and others are severely limited by the military in the aftermath of the coup. Secondly, informal assistance activities are functioning on a wide scale. The second point deserves to be elaborated here. Cross-border aid from neighboring countries, all of which fall under the category of informal aid, have been deployed for decades, and some of them are very systematic operations, based on cumulative knowledge and experience. The target populations for the cross-border assistance from Thailand is estimated to have reached up to a million people.[8] The HO report expects further growth of informal assistance activity in places where official humanitarian projects remain restricted.

Apart from these research findings, the report demonstrates how a remote questionnaire can be useful as a new research method. Relatively safe and efficient, phone surveys should be actively employed in policy advocacy and academic research on Myanmar.

Myanmar’s rich culture of giving has been known for a long time,[9] and the HO survey confirms that this culture is alive in their humanitarian practice; people have been building horizontal networks of aid in flexible and fluid manners. What is needed today on the part of international donors is to recognize and skillfully support these grassroots initiatives where they are effective, rather than rushing in with large-scale interventions.

“Localization” has been a widely recognized trend in the field of humanitarian aid, and the case of Myanmar deserves our attention as a noteworthy example of resilient grassroots practice. The term “localization” may be misleading, however, because Myanmar’s civilian humanitarian networks are not limited to the local level. They are multi-scalar operations, deploying cross-border medic teams, processing international remittances, and operating internet commerce among other activities.

The HO report presents a range of significant findings because of the innovative use of a remote questionnaire, but it tells us little about international remittances from Myanmar’s growing diaspora communities. Sizable remittances from Myanmar expatriate workers to their home country has been recognized by economists for many years.[10] And the active responses from the diaspora communities after the 2021 coup too were widely reported. However, we do not yet seem to have a large-scale quantitative study on the post-coup remittances and their impacts. The HO report states that there is “virtually no coordination” between informal assistance from the diaspora and international organizations; further research is necessary to understand what kind of coordination is possible and desirable.

While international organizations in Myanmar are under the military’s tight surveillance, grassroots humanitarian efforts made by ordinary citizens are remarkably active, widespread, and effective. Understanding these efforts, made by and for the people of Myanmar, will be useful in designing humanitarian programs in other countries and regions around the world.

[1] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Humanitarian Response Plan Myanmar, End-Year Report 2022, 2023, p.4. [2] Décobert Anne, The politics of aid to Burma: a humanitarian struggle on the Thai-Burmese border (Routledge, 2015). [3] HO outsources the remote survey to a private company called GeoPoll (https://www.geopoll.com). [4] Since the SCORE survey methodology is the same regardless of the country covered, the description is not included in the country-specific reports, which are presented on the HO website. (https://www.humanitarianoutcomes.org/projects/core/methodology accessed 2023-11-28) [5] Humanitarian Outcomes, “Survey Questionnaire” (https://www.humanitarianoutcomes.org/projects/core/survey-questionnaire accessed 2023-11-28) [6] Since the exact figures are not presented in the HO report, the figures in this report are based on the bar chart in the report. [7] Humanitarian Outcomes, “Humanitarian Access SCORE Report: Myanmar” (April 2023), p.14. [8] Sullivan, D, Paths of assistance: Opportunities for aid and protection along the Thailand-Myanmar border. (Refugees International, 2022). (https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports/2022/7/11/paths-of-assistance-opportunitiesfor-aid-and-protection-along-the-thailand-myanmar-border accessed 2024-01-17); OCHA, Myanmar humanitarian update No. 19, (June 28, 2022). (https://reliefweb.int/report/myanmar/myanmar-humanitarian-update-no-19-28-june-2022 accessed 2024-01-17) [9] Kawanami, Hiroko, The culture of giving in Myanmar: Buddhist offerings, reciprocity and interdependence (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020). [10] Kubo, Koji, “Evolving informal remittance methods among Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand,” Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 22-3 (2017), pp. 396-413.

Professor, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Yamagata University. After studying philosophy at Oberlin College (USA) and St. John’s College (USA), he moved to Thailand to work for a human rights NGO, before receiving Ph.D from the National University of Singapore. In response to the Myanmar military coup in 2021, he led a crowdfunding campaign to raise 55 million yen for humanitarian aid.

The author gratefully acknowledges the contribution by Tomohito Nakano (Master’s student, School of International and Public Policy, Hitotsubashi University) in finalizing this briefing.