People from the Hopeless Land in the Midst of Endless Conflict

Hnin Htet Htet Aung

(Visiting Researcher, Graduate School of Law, Hitotsubashi University)

August 29, 2022

This is an English translation of “မဆုံးနိုင်တဲ့ ပဋိပက္ခတွေကြားက မျှော်လင့်ချက်မဲ့နေရတဲ့ မြေစာပင်များ,” originally published in ယနေ့ခေတ် နိုင်ငံရေး မဂ္ဂဇင်း (World Today Political Magazine) on June 4, 2022. The original article can be accessed at: https://www.ynkhit.com/မဆုံးနိုင်တဲ့-ပဋိပက္ခတွ/

“If I had not come to be an internally displaced person, I might be having conversations with my friends at this time. Cutting bamboo and making charcoal is our livelihood which cannot make better business, but at least we can make our life happy with families and friends, enjoying a simple life. Now we are scared of seeing any dark things. Sometimes, it seems to me there is nowhere to live if I hear of someone from the neighboring villages, killed by the junta. It is a terrible moment whenever I imagine if my family members or my friends were killed by the military.” These are the words of a 22-year-old IDP man who shared his experience and feelings with the author.

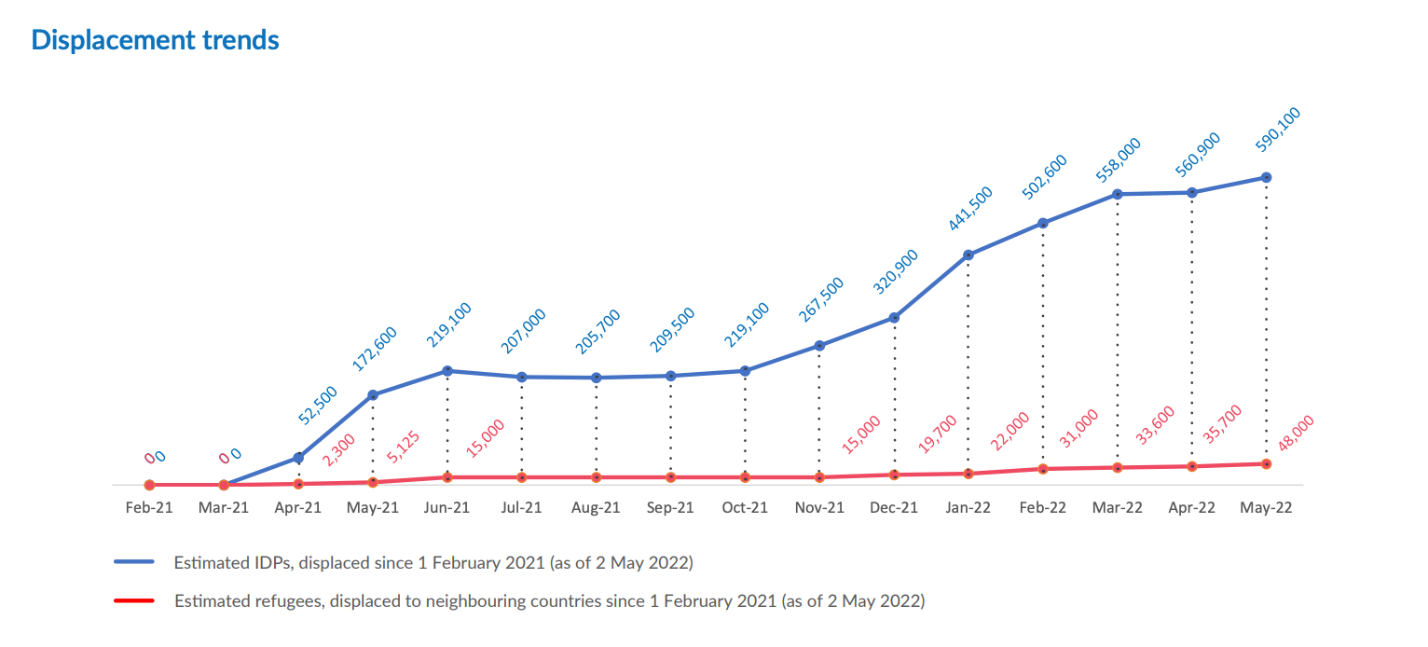

A greatly increased number of IDPs was found after February 2021, on top of large numbers of persons already displaced by 70 years of civil war and internal conflict in Myanmar. According to the findings of the United Nations, that number more than doubled from 370,000 (as of December 2020) to 800,000 after the coup. The number has reached more than 900,000 as of the time of writing in July 2022.

Source: “Displacement trends” from UNHCR, “Myanmar Emergency Update” (May 4, 2022), p.5. https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/92563

Source: “Displacement trends” from UNHCR, “Myanmar Emergency Update” (May 4, 2022), p.5. https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/92563

These people from across Myanmar have to flee their homes to go not only to refugee camps but also to jungles and villages nearby. Among them can be found people of all genders and ages, but the old people and infants suffer more than others. Based on interviews with IDP people, many in their 70s and 80s are still living in danger, saying that they will stay where they are since they don’t want to leave their home.

Ko Aye Chan from upper Burma said that “there are no specific refugee camps and the IDP people have to settle down in tents and near religious buildings. In the meantime, the biggest problem for our people is having no demilitarized zone. Therefore, people have to flee to the southern part if there is a conflict in the northern part. In this case, host communities take care of IDP people for their meals. There are 32 IDP villages in our area and some villages have been completely destroyed. So, they had to live in the fields and the roof is made of thatch while some people have to settle down in their temporary place on the sand. In recent months, the number of IDP people has been increasing and they definitely can’t go to the cities, so helpers like us have to arrange shelters for them. Even if we have money, we cannot buy rice, medicine, oil and salt which are very scarce. Regarding petrol, we have to pay 4,000 to 5,000 Myanmar Kyats for less than a liter.”

Similar to Ko Aye Chan, another person from the mountainous areas of upper Burma who is carrying out relief work for IPDs is also concerned about humanitarian assistance as international organizations including the United Nations are focusing their efforts on conflict sensitivity with less consideration for IDP people. Speaking of the action of the international community and ASEAN, this person stressed that “although they are shouting and shouting about humanitarian issues but in reality, we, our people, have to help each other.”

The military coup left the education sector in a very weak state after February 2021. Despite the school opening season in June, our next generation have to run through the jungle hand in hand with their parents, instead of going to school with their parent’s arm around their shoulder. If they were in school, they might have a snack at break time with their friends, but in practice they have to hide in the caves, under the trees, with hungry stomachs in order to avoid the bombs and guns.

“If I am allowed to go school, I will be a Grade 7 student. I want to study and wish to meet with my friends. At this time, some of my friends are studying in the township level school. In my case, this is my first time to take care of my younger brothers and sisters, since I was apart from my family to study in the township level school in the past,” said an 11-year-old IDP girl.

Among the IPD people, mothers of infants provide the greatest challenge, for the security of their children and themselves. In addition, the parents of adult girls are worried about their daughters’ security while running from the military soldiers. It is even more difficult for those who are fleeing the war in the fields and forests rather than a refugee camp.

A woman who is the mother of seven children also shared her experience that this is her first time being displaced and it was difficult to handle when her children cried in fear. “Once, we had to hide in a brick kiln when the weather was extremely hot and sweaty. But we had no time to pack food and water and it was really hard to dare to go out and eat at meal time. I thought that it is such a hell,” the woman said. She also told the story of how many times they went hungry while fleeing the war.

Regarding communication, a 50-year-old IDP woman said, “We don’t have electricity but there is a motorcycle battery we brought. Using solar power, we can charge the battery. It is very useful in order to charge the handphone to communicate with relatives and friends for information and emergency matters.”

When we compile the list of IDP people, these interviews point out, it is not enough to count just the population in the refugee camps, and IDPs subsisting in the jungle should be counted as well. While our next generation, the school-age children, are drifting away from school and the classroom, our future is drifting with them.

Hnin Htet Htet Aung is a Visiting Researcher at the Graduate School of Law, Hitotsubashi University. Hnin has nine years of experience working in civil society, international non-governmental organizations, and a Singapore-based advisory firm. Before being a visiting researcher, Hnin worked as a program director at Citizen Action for Transparency (CAfT – Myanmar). Prior to that, she was a program manager at the National Coordination Secretariat – Myanmar Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (MEITI) and program officer at Norwegian People’s Aid and other organizations. Through her work, she has supported civil society organizations and their activists. She has published articles about the political situation in Myanmar, women’s rights, transitional justice, collective actions, and freedom of expression, in both Burmese and English. She holds a master’s degree in public administration from Aldersgate College, Philippines and a bachelor’s degree in law from Dagon University, Myanmar.