Countermeasures Against Disinformation Targeting Kurds in Japan and the Design of Counter-Narratives

Jumpei Matsuda

(Master’s student, School of International Public and Policy, Hitotsubashi University)

December 29, 2025

Section 1: Introduction

The Kurdish people, who possess a distinct language, culture, traditions, and a long history, are an ethnic group estimated to number around 30 million. Despite this size, they currently lack an independent state, residing primarily across a region known as “Kurdistan,” which spans the border areas of Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq. Often referred to as the “largest stateless nation,” Kurds are frequently subjected to discrimination and persecution in the countries where they reside. In Japan, most Kurds hold Turkish nationality and live under an unstable legal status, having applied for refugee recognition.

In recent years, disinformation targeting the Kurdish community in Japan has risen sharply, especially online. A key feature of this disinformation is that it not only targets their legal status as “refugee applicants of Turkish nationality” but also attacks their identity as a specific ethnic group – as Kurds. This spread of disinformation implies that the issues facing Kurds in Japan are not just about immigration and legal matters but also about deeper ethnic discrimination.

The purpose of this policy paper is to analyze the current state of this disinformation problem targeting Kurds in Japan and to propose policy recommendations based on an understanding of the underlying factors and the limitations of existing countermeasures. This paper is based on the belief that current efforts are inadequate and limited, and the discussion will focus on how to overcome these shortcomings and develop more effective measures.

The paper first provides an overview of the information environment surrounding Kurds in Japan and its associated problems. Next, it analyzes the actors involved in the dissemination of disinformation, as well as the psychological factors that make people susceptible to it, with a specific focus on the roles of social and personal anxiety. Based on these analyses, this paper proposes design principles for counter-narratives and specific implementation strategies, which, it argues, are more effective.

Section 2: The information environment surrounding Kurds in Japan: Current efforts and their limitations

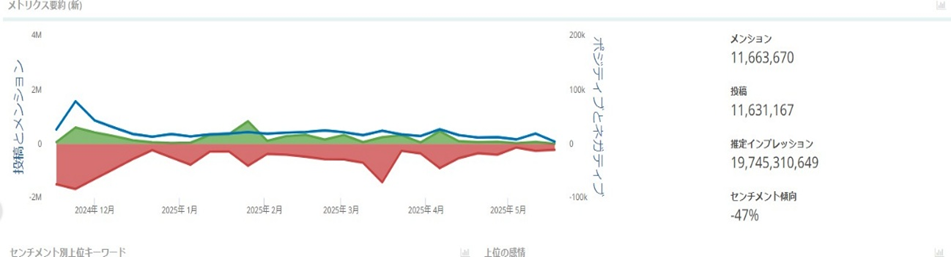

Following a Kurdish-related incident that occurred in Kawaguchi City, Saitama Prefecture, in July 2023, the amount of information about Kurds in Japan on social media platforms skyrocketed. On X (formerly Twitter), the total number of relevant posts over the past decade was 45,000; however, this number exploded to over 4.8 million in roughly a year and a half after the incident. As shown in Figure 1, about 11 million posts that include the word Kurd were made in just six months since December 2024, showing a sharp rise in information about Kurds.

Figure 1: The number of posts regarding “Kurds” (from January 2024 to May 2025)

Source: Made by the author using Quid Monitor.

This rapid growth in information has been accompanied by widespread circulation of both misinformation and disinformation. Much of this disinformation involves inserting malicious misinterpretations or exaggerations into fundamentally accurate facts.[1] Examples include the false claim that Kurdish cultural events were held “without a permit” and the fabrication of nonexistent riot footage.[2]

Such online rhetoric has serious real-world consequences. Anti-Kurdish demonstrations with hate speech have been repeatedly organized near Kawaguchi Station, and the Kawaguchi City office has received numerous protest calls, namely demanding to “expel the Kurds.” It is reported that many of these calls come from outside the city, indicating that non-local people, prompted by online information, are escalating the situation. Tatsuhiro Nukui, a representative of a support organization, warns of the disparity between the internet and reality, cautioning that “if you only look at the internet, it can feel like a ‘Mad Max’ world, where Kurds have taken over Kawaguchi and Warabi.”[3] In reality, however, Turkish nationals (including Kurds) constitute only a small fraction (around 3% as of 2023) of all foreign residents in Kawaguchi, and Japanese nationals commit the vast majority of Penal Code offenses recorded in Saitama Prefecture.[4]

In response to this situation, Kawaguchi City has published a human rights awareness booklet that addresses discrimination and refers to the Hate Speech Elimination Law in its chapter on the human rights of foreign nationals.[5] However, its effectiveness has been limited. This is because city-issued booklets are hard to distribute to the entire population, and they rarely reach those who are not already interested, especially when compared to the sensational information circulating online. Recognizing this distortion in the information environment and the limitations of current measures is the first step toward developing a more effective strategy.

Section 3: Actors in disinformation dissemination and factors of influence

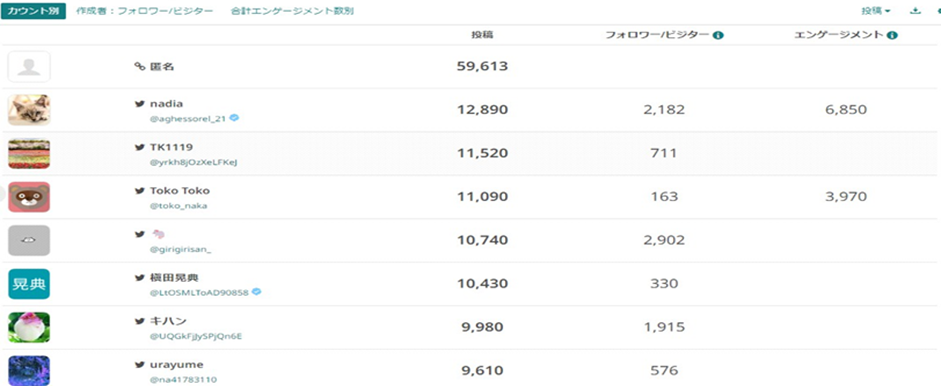

The spread of disinformation targeting Kurds in Japan involves a complex interaction between actors with specific motives and a segment of the population vulnerable to accepting this information. First, this paper identifies the types of actors spreading disinformation by examining X accounts that post relevant terminology, using Quid Monitor to analyze data from various media sources. Then, it analyzes the demographic likely to receive disinformation from these identified actors.

1.Key disinformation dissemination actors: Elements of exclusionism and anti-Kurdish sentiment

Figure 2: Users (including those who reposted) who most frequently posted content containing the terms ‘Kurdish,’ ‘Chinese,’ ‘Korean,’ ‘Chōsen,’ or ‘foreigners’ (from December 2024 to March 2025)

Source: Made by the author using Quid Monitor.

Figure 3: Frequent words in the profiles of users in Figure 2

| keywords | English | ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 日本 | Japan | 14% |

| 好き | Like | 11% |

| 大好き | Love | 6% |

| 日本人 | Japanese | 4% |

| 無言フォロー | Silent follow | 4% |

| いい | Good | 3% |

| 趣味 | Hobby | 3% |

| 反対 | Oppose | 3% |

| アカウント | Account | 3% |

| 情報 | Information | 3% |

| 推す | Support | 2% |

| 守る | Protect | 2% |

| ゲーム | Game | 2% |

| 呟く | Post | 2% |

| アニメ | Anime | 2% |

| 世界 | World | 2% |

Note: English column is added through the translation process.

Source: Made by the author using Quid Monitor

Figures 2 and 3 suggest that the actors disseminating disinformation concerning Kurds hold nativistic or xenophobic beliefs. Their profiles frequently feature words like “Japan” and “Japanese,” and their posts repeatedly include discriminatory rhetoric not only against Kurds but also against Chinese and Koreans. This indicates a tendency for these actors to target multiple foreign groups, rather than limiting their focus to a single foreign collective.

Furthermore, a specific cluster of accounts was found to focus intensely on posting negative content directed exclusively at Kurds.

Figure 4: Users (including those who reposted) who most frequently posted content referring only to ‘Kurdish’ (excluding ‘Chinese,’ ‘Korean,’ ‘Chōsen,’ and ‘foreigners’)

Source: Made by the author using Quid Monitor.

Unlike the first group, this cluster does not typically mention other foreign nationals but directs strong hostility solely toward Kurds. Notably, a prominent figure, @ishiitakaaki, has appeared on the Turkish state media outlet TR[6] and has been presented as a researcher on Kurdish affairs in a newspaper from Turkish-only recognized North Cyprus.[7] Turkey is known to carry out influence operations in Europe and the Middle East, using various forms of disinformation to discredit Kurds.[8] Ishii himself has revealed that Turkish media asked him to write articles critical of Kurds.[9] This indicates that these types of accounts might be part of an influence operation aimed at supporting the Turkish government’s stance and intentionally damaging the image of Kurds within Japan.

2.The psychological vulnerability of the “floating/apathetic electorate”: Personal and social anxiety

In the spread of disinformation, the role of individuals without strong political beliefs is as important as that of actors with clear political motives. Although not visually shown in the data, it is likely that the “floating electorate” or the “apathetic segment”, those lacking strong political convictions, contribute to both the spread and acceptance of false information. The vulnerability of the “floating/apathetic segment” to disinformation, especially exclusionary narratives targeting Kurds in Japan, is deeply rooted in the “anxiety” they experience. This anxiety can be broadly divided into “personal anxiety” and “social anxiety.”

“Personal anxiety” refers to individual psychological instability, including feelings of uncertainty about the future, insecurity about one’s livelihood, loneliness, and unmet needs for recognition. People experiencing high personal anxiety are stressed by a vague sense of unease about social and economic conditions. They often look for a clear cause or an enemy to relieve this anxiety.[10] This mental process makes it easier for them to blame external groups, like foreigners or immigrants, which simplifies the problem and provides reassurance. As a result, people with personal anxiety tend to be vulnerable to xenophobic talk and conspiracy theories.[11] It has been noted that during economic downturns, the view of immigrants as rivals or threats grows, increasing xenophobia.[12] This is called scapegoating, a psychological process where people vent their frustration or social dissatisfaction by targeting vulnerable groups.[13] Additionally, the fear of being isolated can lead individuals to spread disinformation, as not sharing false information within an SNS group can reduce their interaction with other members.[14]

Social anxiety, on the other hand, refers to the apprehension that the social group itself is in danger, such as concerns about worsening public safety or the breakdown of cultural order. This connects to Group Threat Theory,[15] where vague fears and anger, like the worry that “public safety might worsen because of Kurds,” stem from this type of anxiety.

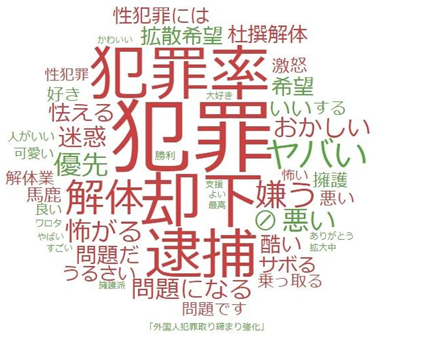

Figure 5: Terms frequently co-occurring with ‘Kurdish’ in posts on X (formerly Twitter)

Source: Made by the author using Quid Monitor.

As shown in Figure 5, a visualization of the words posted alongside “Kurds” on X reveals that “crime (犯罪),” “crime rate (犯罪率),” “rejection (却下)”, and “arrest (逮捕)” are among the most frequently used terms. This objectively confirms that the disinformation is specifically designed to resonate with those who harbor “social anxiety.” The repeated use of these terms creates the impression that the entire Kurdish community poses a threat to social stability, fostering an environment for exclusionary sentiment.

Section 4: Deepening persona analysis

To construct effective counter-narratives against disinformation, it is necessary to identify the target audience (personas) most susceptible to its influence. This is because effective counter-narratives can be designed based on clearly defined characteristics. Therefore, this section deepens understanding of the segment vulnerable to disinformation about Kurds in Japan by developing specific personas based on anxiety types and recent social trends, to improve the precision of the counter-narrative strategy.

Persona 1: Ms. Hayashi (“personal anxiety” segment)

Profile: A woman in her 30s, a non-regular employee living in Tokyo. She is relatively apathetic about politics and primarily gathers information from social media. Her position as a non-regular employee causes her to harbor vague personal anxieties about the future (economic stability, career path, social recognition, etc.). She is susceptible to emotionally appealing information and visually impactful content. When exposed to sensational disinformation about Kurds, she may not scrutinize the content deeply but simply feel “it’s somehow scary” or “there might be a problem,”[16] potentially contributing to its spread through reposts.

Rationale and representativeness: The rate of non-regular employment for women in Japan is structurally high. The number of female non-regular employees significantly exceeds that of males. As of January–March 2023, there were 14.37 million female non-regular employees compared to 6.75 million males, a difference of more than double. Furthermore, non-regular employees make up 53.7% of all female employees, compared to 22.5% for males. This gap indicates a structural background where women are more likely to face economic instability. Similar trends were observed in the 2024 average.[17] Non-regular employment often leads to financial instability, which can contribute to personal anxiety. Ms. Hayashi represents a contemporary type of young to middle-aged urban woman who feel economic and social pressure but attempt to connect with society through social media. This demographic, precisely because they lack a strong, defined ideology, may be vulnerable to emotionally charged information, such as content portraying Kurds as symbols of social instability.

Relevance to the Kurdish issue: When Ms. Hayashi’s personal anxiety connects with disinformation targeting a specific group like the Kurds (e.g., fragmented videos or stories suggesting Kurds threaten the peaceful Japanese routine), that anxiety can be perceived as a tangible “fear,” leading to the acceptance and dissemination of disinformation.

Persona 2: Mr. Sato (The “social anxiety” segment)

Profile: Mr. Sato is a man in his 50s, a company employee living in the suburbs. He holds conservative political views. He harbors strong dissatisfaction and anxiety regarding the recent opacity of politics and the rapid pace of social change. He places a high value on security and order. Exposure to fragmented information and radical rhetoric leads him to perceive the presence of foreign communities, particularly Kurds, as a threat to social order and traditional Japanese values, generating strong anger and vigilance.[18]

Rationale and representativeness: Mr. Sato is likely to accept narratives portraying Kurds as “outsiders who do not follow the rules” as the “truth” that validates his anxieties and helps him envision the restoration of the social status quo.

Relevance to the Kurdish issue: Mr. Sato’s strong desire for social order and his dissatisfaction with the current situation, when exposed to negative information about Kurds (e.g., crime, cultural friction, illegal residency issues), can lead him to perceive them as “problematic elements” undermining social stability, and justify exclusionary sentiments.

These two personas are crucial for concretely understanding the psychological mechanisms through which disinformation about Kurds in Japan is accepted and spread. Disinformation penetrates the personally anxious segment like Ms. Hayashi through an emotional and empathetic approach, while it infiltrates the socially anxious segment like Mr. Sato through an approach that incites “crisis” and “threat.”

Section 5: Design principles and strategies for counter-narratives

To counter disinformation, particularly exclusionary rhetoric, targeting Kurds in Japan, it is essential to construct counter-narratives that correspond to the different forms of anxiety held by the “floating and apathetic electorate” analyzed in the previous chapter, alongside concrete measures to foster coexistence. This section examines effective counter-narrative strategies tailored to each persona type.

A. Counter-narrative strategy for personal anxiety (Ms. Hayashi type): Empathy and humanization

For individuals like Ms. Hayashi, who are susceptible to vague fears arising from personal anxiety, an effective strategy is to portray Kurds not as an abstract “foreigner” but as a “relatable individual,” and foster a sense of human connection.

Use of visuals: Works like the film My Small Land, which realistically depicts the daily lives and struggles of young Kurds in Japan, have the power to let viewers vicariously experience their lives and evoke empathy.[19] Therefore, consistently posting one-minute trailers of such films on social media platforms is a potentially effective method. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) also points to the potential of films to deepen empathy and understanding toward migrants.[20]

Visual-centric social media platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube would be effective media for this purpose. The goal is to share photos and short videos of the daily lives of Kurds in Japan (e.g., cooking traditional food, child-rearing, work, participating in festivals, and efforts to learn Japanese). Specifically, videos with subtitles are an effective way to deliver a message widely, given that 85% of users reportedly watch videos on social media platforms with the sound muted.[21]

Visualization of daily life and efforts to blend in: Highlighting the efforts of Kurds to integrate into Japanese society, such as their diligent study of the Japanese language, is effective in conveying that they are not “an outsider” but rather “neighbors who live together.”

Figure 6: A youth softball club in Kawaguchi City, Sa Prefecture

Source: Suzuki, Akiko, “Kawaguchi de tomo ni sodatsu gaikoku rutsu no kodomotachi: kari homen no mibun ga shingaku ya yume o habamu yoin ni [Growing Up Together in Kawaguchi: How Provisional Release Status Hinders the Education and Dreams of Children with Foreign Roots],” The Asahi Shimbun Globe+ (May 14, 2023). (https://globe.asahi.com/article/14905381 Accessed on 2025-11-25)

Figure 7: Kurdish children studying at a Japanese language class in Kawaguchi City, Saitama Prefecture

Source: Zainichi Kurudo jin to tomo ni [Together with Kurds in Japan] “10/15 no Nihongo kyoshitsu [10/15 Japanese Language Class]” (October 19, 2023). (https://kurd-tomoni.com/japaneseclassroom20231015/ Accessed on 2025-11-25)

B. Counter-narrative strategy for social anxiety (Mr. Sato type): Sharing norms and risk presentation

For individuals like Mr. Sato, who highly value the maintenance of social order and safety, and who are susceptible to the perception of threat that “foreigners will disrupt society,” what is necessary is a narrative to alleviate their anxiety and demonstrate that Kurds respect Japanese social rules and values and are capable of coexistence.

Stories of norms and cultural adherence: This includes introducing instances where Kurds actively uphold community rules, participate in crime prevention patrols, and respectfully engage with Japanese culture and festivities.

Figure 8: Kurds in Kawaguchi City wearing yukata[22]

Source: Tokyo Shimbun, “Kurudo jin to kyosei e gakusei koryu: kumagaya no rissho dai de seminaa, nayami ya sodan ya minzoku isho shokai [Student Exchange for Coexistence with Kurds: Seminar at Rissho University in Kumagaya, Sharing Concerns, Providing Consultation, and Introducing Ethnic Costumes]” (June 21, 2024). (https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/335031 Accessed on 2025-11-25)

Figure 9: Joint patrol between police and the representative director of the Japan Kurdish Cultural Association near JR Higashi-Kawaguchi Station

Source: Saitama Shimbun, “‘Ruru shiranai hito mo… hatarakikaketai’: saitama kenkei to kurudo jin ra, kawaguchi de godo patororu, chiiki de no kyosei unagasu [‘Some People Do Not Know the Rules… We Want to Reach Out’: Saitama Prefectural Police and Kurds Conduct Joint Patrol in Kawaguchi to Promote Local Coexistence]” (November 7, 2023). (https://www.saitama-np.co.jp/articles/53513 Accessed on 2025-11-25)

Presenting the risk of nativism (appeal to emotion): This strategy introduces the perspective that exclusionary behavior toward foreigners can, in itself, negatively impact Japan’s overall stability and security, appealing to emotion. The counter-narrative used in the Okinawa gubernatorial election to combat disinformation provides a useful reference.[23]

A lack of an environment where different sides can stay connected and cooperate on defense is dangerous. Just as isolated villages were left without relief supplies after earthquakes, social rifts can leave the Japanese people stressed, turning against each other. Instead of uniting to confront true threats, we may each face the enemy alone and in isolation.

This uses a message that appeals to a sense of common crisis. Applying this concept, disseminating a question through the Japanese editions of international news organizations and highly reliable websites could reach conservative-minded segments like Mr. Sato, who prioritize order: “If we expel certain people, whether they are Kurds or anyone else, and divide society, Japan will become weak from within. Therefore, we should choose the path of not creating an internal enemy but strengthening the country by having people from diverse backgrounds support one another.”

C. Common strategy: Creating opportunities for contact (Contact Hypothesis)

One effective approach for both personas can be based on Gordon Allport’s Contact Hypothesis.[24] Positive contact experiences with other groups are known to reduce stereotypes and prejudice.

Promoting positive contact: This strategy creates opportunities for positive and cooperative interactions between Kurdish residents and local residents through joint participation in local festivals and sports events, school exchange programs, and workplace collaboration. Organizing and implementing cultural events that introduce Kurdish culture, with the active participation of local residents, is also an effective approach. Within Japan, there are diverse examples of initiatives promoting multicultural coexistence and contact, such as Hamamatsu City’s “Hamamatsu Multicultural Coexistence MONTH”[25] and the participation of foreign residents in Kusatsu City as “functional fire corps members” for disaster support.[26]

Section 6: Conclusion

The problem of disinformation and hate speech concerning Kurds in Japan is not merely one of human rights violations toward a minority group. Still, it challenges the very nature of Japan’s multicultural society. This paper has analyzed the rapidly changing information environment underlying this issue, the diverse actors involved in the dissemination of disinformation, and the psychological mechanisms by which it is accepted. Based on this, it argued for the importance of counter-narrative strategies to combat the spread of disinformation, especially by anxious segments. These strategies include fostering empathy to address personal anxiety, mitigating the perception of threat to address social anxiety, and promoting interaction based on the Contact Hypothesis as a strategy effective for both, while drawing on domestic and international examples.

Based on this analysis and these proposals, the future challenges, outlook, and specific policy recommendations are outlined below.

1.Validation and refinement of counternarrative strategies

It is essential to refine the counter-narrative strategies by using experiments and surveys to clarify which messages are most effective for which persona type (e.g., empathy-evoking vs. norm-presenting). Message design and effectiveness measurement should be conducted cautiously to avoid the “backfire effect,” where attempts to correct strongly held disinformation inadvertently reinforce those beliefs.

2.Strengthening efforts to address institutional challenges faced by Kurds in Japan

The Japanese government should strengthen institutional support for Kurds in Japan by revising the unstable provisional release system, establishing pathways to stable residency status, and improving access to medical care, education, and employment. Stabilizing their legal status and reducing their “invisibility” and anxiety forms the foundation for eliminating the breeding ground for disinformation and discrimination.

3.Institutional and social support to strengthen the foundation for a multicultural society

The national and local governments should implement fundamental measures to address the structural issue of the high rate of non-regular employment among women. By promoting stable employment support and improving working conditions for women, the government can reduce the personal anxiety caused by the instability of one’s livelihood that non-regular employment often entails. This will create a social environment less susceptible to disinformation. Simultaneously, the national and local governments should provide financial and technical support to initiatives that promote multicultural coexistence and create opportunities for positive contact.

【English Translation】

Takahiro Nakajima (Master’s student, Graduate School of Law, Hitotsubashi University)

[1] Denno Jingai, “Kurudo-jin ga Nihon no onsen bunka o kowasu to sarete iru shashin wa mizugi chakuyō eria de no shashin da yo [The Photo Alleged to Show Kurds ‘Ruining Japanese Onsen Culture’ Was Actually Taken in a Swimsuit-Required Area],” (June 2, 2025). (https://nou-yunyun.hatenablog.com/entry/2025/06/02/180000 Accessed on 2025-11-25) [2] Japan Fact-Check Center, “Kurudo jin ga shiyo kyoka wo torazu ni koen de katte ni omatsuri? Nyusu eizo ni kyogi no tepoppu wo tsuika, fakuto chekku [Kurds Hold a Festival in a Park without a Permit? Video Footage Includes False Captions: Fact-Checking],” (August 20, 2024). (https://www.factcheckcenter.jp/fact-check/media/false-kurds-hold-festival-without-permit/ Accessed on 2025-11-25) [3] nippon.com, “Saitama: Zainichi Kurudo-jin no ima: Boso suru heito wa tomaranai no ka [The Present Situation of Kurds in Japan: Can the Escalating Hate Be Stopped?],” (October 4, 2024). (https://www.nippon.com/ja/in-depth/d01048/ Accessed on 2025-11-25) [4] Ibid. [5] Kawaguchi City, “Jinken keihatsu sasshi: Minna de manabu jinken mondai (Reiwa 7 nen 5 gatsu kaitei) [Human Rights Awareness Pamphlet: Learning Human Rights Issues Together (Revised May 2025)],” Kawaguchi City. (https://www.city.kawaguchi.lg.jp/soshiki/04010/020/15/15.html Accessed on 2025-11-25) [6] TRT Global, “Japan yatangaza kufungia mali za kundi la kigaidi la PKK,” (May 14, 2024). (https://trt.global/afrika-swahili/article/18154643 Accessed on 2025-11-25) [7] Yeni Bakış, “Japon gazeteci Ishii Takaaki kimdir?”(May 12, 2024). (https://www.yenibakishaber.com/japon-gazeteci-ishii-takaaki-kimdir Accessed on 2025-11-25) [8] Fazıl Alp Akiş,“Turkey’s troll network,” Heinrich Böll Stiftung (March 21, 2022.)(https://eu.boell.org/en/2022/03/21/turkeys-troll-networks Accessed on 2025-11-25) [9] Posts on X by @ishiitakaaki (2025/2/22). (https://x.com/ishiitakaaki/status/1893068690478035126 Accessed on 2025-11-20) [10] Adela Černigoj, “The Influence of Culture and Intercultural Contact on Neo Racism and Ethnocentrism,” Psychological Studies, 67-4 (2022), pp. 447-458. [11] Darrell M. West, “How to Combat Fake News and Disinformation,” Brookings Institution, (December 18, 2017). (https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-to-combat-fake-news-and-disinformation/ Accessed on 2025-11-25) [12] Shimokubo, Takuya, “Shitsugyo ritsu ga nihonjin no haigai ishiki ni ataeru eikyo no (sai) kensho: Shakai chosa deta no niji bunseki o tsujite [Analysis of the Effect of the Unemployment Rate on Xenophobia in Japan Based on Cumulative Social Survey Data],” Japanese Sociological Review, 72-3 (2021), pp. 312-326. [13] D. Vincent Riordan, “The Scapegoat Mechanism in Human Evolution: An Analysis of René Girard’s Hypothesis on the Process of Hominization,” Biological Theory, 16-4 (2021) pp. 242-256. [14] M. Asher Lawson, Shikhar Anand, and Hemant Kakkar, “Tribalism and Tribulations: The Social Costs of Not Sharing Fake News,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152-3 (2023), pp. 611-631. [15] A sociological theory arguing that when a majority group perceives its economic, political, or social status as being threatened by a minority group, it becomes more likely to exhibit heightened prejudice or discrimination against that minority. Herbert Blumer, “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position,” The Pacific Sociological Review, 1-1 (1958), pp. 3-7. [16] Yuna Yokosawa and Naoko Shinoda, “Kogekiteki tsuito ni taisuru kakusan kodo sokushin yoin ni kansuru tansakuteki kenkyu [An Exploratory Study of Factors Promoting the Spread of Aggressive Tweets],” Annual Letters of Clinical Psychology in Shinshu, 21 (2022), pp. 99-114. [17] Employment Environment and Equal Employment Department, “Reiwa 5-nenban Hataraku josei no jijō [Situation of Working Women, 2023 Edition],” Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/koyoukintou/josei-jitsujo/dl/23-01.pdf Accessed on 2025-11-25) [18] William J. Brady, Julian A, Wills, John T. Jost, Joshua A. Tucker, Jay J. Van Bavel, “Emotion Shapes the Diffusion of Moralized Content in Social Networks,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114-28,(2017), pp. 7313-7318. [19] “My Small Land website”. (https://mysmallland.jp/ Accessed on 2025-11-25) [20] IOM, “New Data Reveal: Films Fight Xenophobia, Movies Counter Misinformation about Migrants,” (May 29, 2020). (https://www.iom.int/news/new-data-reveal-films-fight-xenophobia-movies-counter-misinformation-about-migrants Accessed on 2025-11-25) [21] DIGIDAY henshubu [DIGDIG editorial board],“85% no Facebook doga wa ‘muonsei’ de saisarete iru rashii [Apparently, 85% of Facebook Videos Are Played Without Sound],” DIGIDAY Japan (May 26, 2016). (https://digiday.jp/platforms/silent-world-facebook-video/ Accessed on 2025-11-25) [22] The second woman from the right is wearing an outfit designed after traditional Kurdish ethnic dress. [23] Naoki Moriyama, “An Analysis of Counter-Narratives to Disinformation in the 2018 Okinawa Gubernatorial Election,” GGR Issue Briefing No. 102 (October 14, 2025). (https://ggr.hias.hit-u.ac.jp/en/2025/10/14/consideration-of-counter-narratives-against-false-information-in-the-2018-okinawa-prefectural-gubernatorial-election/ Accessed on 2025-11-25 [24] Shigemi Ohtsuki, “Gaikoku jin sesshoku to gaikoku jin ishiki: deta ni yoru sesshoku kasetsu no sai kento [Foreign Contact and Attitudes toward Foreigners: A Re-examination of the Contact Hypothesis Using Data],” JGSS de mita Nihonjin no ishiki to kodo: Nihon-ban General Social Surveys kenkyu ronbunshu [Japanese Attitudes and Behaviors as Seen in the JGSS: Japanese General Social Surveys Research Paper Series], 5 (2006), pp. 149-159. [25] Hamamatsu City, “Hamamatsu tabunkakyosei, kokusaikouryu potarusaito [Hamamatsu Multicultural Coexistence and International Exchange Portal Site].” (https://www.hi-hice.jp/ja/ Accessed on 2025-11-25) [26] Kusatsu City, “Zenkoku hatsu, gaikokujin kinoubetsu shobo danin no kanosei: sasaerareru gawa kara sasaeru gawa e [Japan’s First Function-Based Firefighting Unit for Foreign Residents: From Being Supported to Becoming Supporters].” (https://www.pref.shiga.lg.jp/file/attachment/5497337.pdf Accessed on 2025-11-25)

Junpei Matsuda is a master’s student in the School of International and Public Policy, Hitotsubashi University. His research focuses on disinformation and influence operations carried out by authoritarian states, with a particular interest in public–private partnerships as a countermeasure to influence operations. He participated in the GGR Intensive Seminar held in the summer of 2024.