An Analysis of Counter-Narratives to Disinformation in the 2018 Okinawa Gubernatorial Election

Naoki Moriyama

(Staff at an international consulting firm)

October 14, 2025

1. Introduction

Okinawa is facing a critical juncture in the fight against disinformation.[1] In recent gubernatorial elections, the spread of highly partisan disinformation on social media has become so widespread that local newspapers have established dedicated response teams.[2] According to the RAND Corporation, Japan, one of the US allies, is an attractive target for Chinese disinformation efforts to expand influence in the Indo-Pacific. The RAND Corporation points out that Japan harbors resentment toward the US military presence in Okinawa, which China may exploit through disinformation campaigns.[3] In recent years, an increase in official Chinese government statements regarding Okinawa has also been observed.[4] These developments suggest that misleading discourses about the relationship between China and Okinawa could spread widely, and that disinformation could exacerbate domestic political polarization during elections.

In such a volatile information environment, the public’s ability to assess and interpret information is under scrutiny. As social media becomes embedded in everyday life, examining how society can respond to the risks posed by disinformation is essential. This article analyzes the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial election as a case to explore potential countermeasures to the spread of disinformation on social media.

2. Okinawa Gubernatorial Election and X

It is not uncommon for information that discredits candidates to spread on social media during election campaigns. For instance, NHK reported a case during the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial election (contested by Denny Tamaki, who opposed the relocation of the US Futenma base to Henoko, and Atsushi Sakima, who prioritized economic growth) where a university student was misled by disinformation.[5] While undecided about who to vote for, the student found a post on X (formerly Twitter; hereafter, “X”) that contained false information. The student shared the post with friends and was further influenced by similar misleading content. The students realized they had been misled by reading a newspaper article identifying the post as disinformation. One specific example of such disinformation involved claims that “Tamaki is an agent of China,” linking the candidate to the Chinese government. While distinguishing between malicious disinformation and unintentional misinformation is often difficult, this case illustrates how undecided voters can be swayed by unverified or false content.

This article focuses on such disinformation: specifically, narratives falsely associating candidate Tamaki with China during the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial election.

A search on X using the keywords “Denny China’s agent (デニー 中国の手下)” reveals numerous posts suggesting that China is controlling Denny Tamaki. At the top of the search results was Post A (see Table 1), which, as of December 9, 2023, had been reposted 2,576 times and received 8,097 likes. The user who posted it has 100,000 followers on X and typically receives around 100 likes per post, indicating significant reach. As of February 11, 2024, the post had been reposted 2,658 times, suggesting that it continues to circulate actively despite being initially posted on August 25, 2022.

Table 1: Examples of posts

| Posts | Reposts | Likes | |

| Post A | 中国にミサイルぶち込まれた沖縄で中国の手下の玉城デニーが知事選で勝ったらもうどうしたら良いかわかんないわ俺。沖縄県民各位、今回は『佐喜真淳』一択だぞ。それ以外は、ガチで家族と自分の命を危険に晒す選択だと思ってください。 | 2,576 | 8,097 |

| Post B | 共産党若手がデニーを『デニーさん』と呼び安倍総理を『アベ』と呼んでいたのが印象に残った。中国の手下に敬意を払う共産党員。コイツら排除しないと日本は食い荒らされるなと実感した。 | 68 | 354 |

| Post C | 沖縄に中国がきてしまう!デニーは中国の手下です! #沖縄 | 39 | 95 |

| Post D (quoted by Post C) |

沖縄県の皆さん、投票に行こう。中国を宗主国と崇めるとどうなるか香港を参考に想像しよう。香港で何が起きたか。欧米のメディアが伝えた香港の映像。今回の選挙は沖縄の未来に大影響を及ぼす分岐点。知事が誰になるかは沖縄の未来に直結。昨日の香港、明日の沖縄を阻止しよう #沖縄県知事選挙 #拡散 | 2,616 | 5,475 |

Source: made by the author based on the following posts. Post A(@CYXuAXfGlfFzZCT), posted at 20:49 on August 25, 2022, (https://X.com/CYXuAXfGlfFzZCT/status/1562769219590422528?s=20)(Accessed on 2023-12-9); Post B(@Empire_Yamato), posted at 12:26, on May 30, 2020, (https://twitter.com/Empire_Yamato/status/1266571582907924480 )(Accessed on 2024-3-13); Post C(@takaatchiba), posted at 8:21, on September 6, (https://twitter.com/takaatchiba/status/1566929517498621952)(Accessed on 2024-3-13); Post D(@KojiHirai6, cited by Post C), posted at 17:42, on September 5,(https://twitter.com/KojiHirai6/status/1566708429057507328)(Accessed on 2024-3-13)

Some of the widely shared posts were similar in content, such as Post B in Table 1, which replied to another (now-deleted) post by asserting that Tamaki is an agent of China while also criticizing members of the Communist Party. Another example is Post C, which quoted Post D from Table 1. While the original quoted post did not explicitly state that Tamaki is an agent of China, the quoting post implied it. These posts share underlying themes that depict Tamaki as an agent of China. The following sections analyze what narratives are constructed by disinformation that associates Tamaki with China, based on the mentioned posts.

3.Analyzing the Narrative Constructed by Disinformation

What kind of narratives do the posts above construct, based on the frame that Denny Tamaki is an agent of China? Drawing from the content of these posts, the narrative suggests that Tamaki maintains illicit ties with the Chinese government and does not act in the interests of Okinawa or Japan. It appears that disinformation spreaders aim to construct narratives that Okinawa will fall under Chinese control if Tamaki’s camp wins the election. This narrative may also help widen social divisions within Okinawa and promote hate speech toward the region.

Tamaki has indeed made contact with China and exchanged information. For example, during a visit to China on July 4, 2023, he visited the tombs from the Ryukyu Kingdom era and emphasized the historical ties between Okinawa and China.[6] Such diplomatic activities suggest an intention to build amicable relations between Okinawa and China.

However, these actions alone are insufficient grounds to claim that Tamaki is under the influence of the Chinese government. For instance, during his 2023 visit to China, a video of Tamaki dancing at a banquet was circulated on X and received critical comments.[7] At most, such footage may indicate that he does not harbor negative feelings toward China.

Nevertheless, posts supporting the claim that Tamaki is an agent of China continue to circulate on X. Following the publication of a report by the Institute for Strategic Research (IRSEM, France) on China’s global information warfare, one passage was frequently cited. The report noted that “as evidenced by the election of Denny Tamaki as governor in October 2018, a large part of Okinawa is anti-Tokyo and anti-central government.”[8] This observation was subsequently used as justification to label Tamaki as an agent of China.[9] However, the report provides no evidence of illicit ties between Tamaki and the Chinese government. It is likely that “anti-Tokyo” was immediately interpreted as “anti-Japanese,” thereby fueling the assumption of ties with China. This narrative seeks to frame Tamaki as a political actor who does not work for the benefit of Okinawa or Japan, and such instills fear that Okinawa could fall under Chinese control. Such manipulation of public perception can be categorized as a form of digital influence operation known as “perception hacking.”[10]

Further analysis of the linguistic features of the posts[11] listed in Table 1 reveals a familiar pattern: the use of violent language. Posts A, B, and C, for instance, contain expressions such as “missile strike,” “danger,” “eliminate,” “devoured,” “koitsu (in Japanese, a rude way to refer to somebody),” and “agent,” all of which carry aggressive or hostile connotations. These posts appear to disseminate anti-Tamaki narratives by employing emotionally charged and violent rhetoric.

In sum, the narrative portraying Tamaki as engaged in illicit ties with China and as a political actor who threatens the interests of Okinawa and Japan is being amplified through the use of violent and inflammatory language.

4. Potential Disinformation Spreaders and Target Personas

For the purpose of considering effective countermeasures against disinformation in future Okinawa gubernatorial elections, this section analyzes the likely sources of disinformation (i.e., those who post narratives such as those described above) and the personas targeted by such disinformation campaigns.[12]

The disinformation spreaders are likely domestic individuals or groups in Japan who, based on the previous hypotheses, seek to discredit the pro-Tamaki “All Okinawa” coalition and actively spread anti-China sentiments.[13]

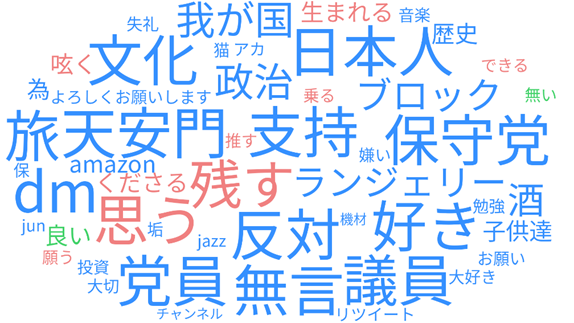

This study assumes that the target persona of such disinformation is someone who harbors preexisting dissatisfaction with anti-base movements in Okinawa or China and actively engages with social media platforms. Such individuals will likely focus on the Okinawa gubernatorial election, which is often a flashpoint for China-related issues. An examination of the profiles of accounts that reposted the example shown in Figure 1 reveals that many users express support for specific political parties, such as the Japan Conservative Party, and share anti-China sentiment (see Figure 1).[14] Their profiles frequently include nationalistic expressions such as “our country” and “Japanese people,” as well as terms like “Tiananmen,” reflecting a critical stance toward China.

Based on this observation, it is possible to assume several characteristics of the X-based community targeted by disinformation narratives. First, even outside of election periods, when the threat of election-related disinformation is relatively low, an echo chamber is formed by accounts that share similar views and ideologies. Second, this echo chamber amplifies the reach and influence of individual posts. Third, this heightened influence increases the risk that foreign actors may exploit the community during election periods to disseminate disinformation. In summary, the threat of disinformation in the echo chamber–prone social media environment is considerable, particularly given its potential to be exploited by foreign actors.

Figure 1: Analysis by User Local Text Mining Tool

Source: Made by the author.[15]

The primary target group for disinformation is the voting population of Okinawa, especially those who remain undecided about which candidate to support. It is assumed that such discourses spread within various filter bubbles—groups formed by shared opinions—and beyond them. As elections are a widely shared topic of interest, individuals may use platform search functions to access content beyond their usual filter bubbles, thereby encountering posts from unfamiliar filter bubbles.[16]

According to user statistics released by X, the largest proportion of X users by occupation includes “executives, company employees, and public servants.”[17] Given that elections concern the entire voting population and these occupational groups show high engagement with X, it can be inferred that disinformation is particularly likely to target the group of occupations mentioned above. Furthermore, the same statistics show that working adults frequently use the platform’s search function. As such, disinformation narratives tagged with hashtags like “#沖縄総選挙(Okinawa Gubernatorial Election)” are likely to appear frequently in search results and gain visibility.

However, a potential discrepancy exists between the seemingly intended targets and those influenced by these narratives. In addition to voters in Okinawa, conservative users on the Japanese mainland may also be targeted. These narratives may aim to discredit the All Okinawa coalition and its left-leaning supporters while promoting conservative unity and contributing to broader political polarization. It is also plausible that the narratives are intended to draw moderate swing voters toward the conservative bloc.

Thus, if it is understood that discourse surrounding the Okinawa gubernatorial election is being inappropriately leveraged amid ideological conflict, disinformation can be seen to operate with both primary and secondary targets. The primary target is the Okinawan electorate, which directly participates in the gubernatorial election. Meanwhile, in the dissemination process, the narratives serve as material for partisan discourse, making the broader Japanese public a secondary target of the disinformation campaign.

5. Constructing Counter-Narratives

This section considers effective countermeasures to disinformation targeting ideologically opposing groups during the Okinawa gubernatorial election, focusing specifically on developing counter-narratives.[18] As with the narratives disseminated through disinformation, effective counter-narratives must be emotionally resonant and conducive to receiving likes and shares on platforms like X. However, since the political discourse on X is already prone to polarization, introducing additional politically charged narratives may risk furthering societal divisions. Therefore, it is assumed that counter-narratives that do not directly address the election itself may be more effective.

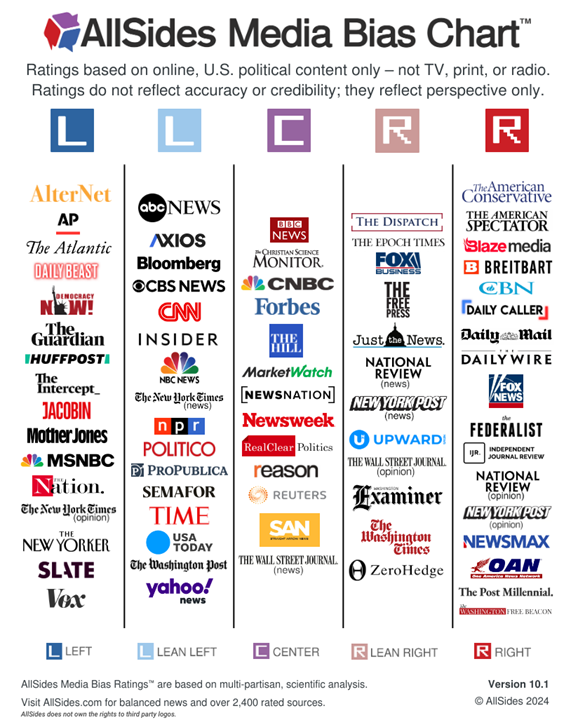

Ideally, actors with substantial reach and credibility should disseminate counter-narratives to conservative audiences. However, it is not easy to envision a scenario in which individuals from opposing ideological camps actively hear voices from the other’s perspective. In Japan, most domestic media outlets have long-established political positions, and certain audiences may reject a piece outright simply upon seeing the name of the publishing newspaper. In contrast, Japanese-language editions of foreign media outlets may have greater potential to bypass entrenched perceptions of domestic media bias and deliver messages that reach broader audiences. Thus, this paper proposes that the Japanese-language editions of foreign media outlets are suitable actors for disseminating counter-narratives. These include BBC NEWS Japan, The Wall Street Journal Japan Edition, and CNN.co.jp. Each platform provides translations and editorial content from international sources by Japanese teams. However, it is important to acknowledge that even foreign media outlets possess their own ideological bias, whether left- or right-leaning (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Political positions of foreign media

Source: AllSides, “The AllSides Media Bias Chart” (2024).

(https://www.allsides.com/media-bias/media-bias-chart Accessed on 2025-4-9)

This paper proposes submitting op-eds containing counter-narratives to the Japanese-language editions of foreign media outlets, with dissemination through their respective social media accounts as a central strategy. Assuming the narratives constructed by disinformation intend to draw Japan’s moderate swing voters toward the conservative camp, articles published by these foreign media platforms are expected to reach this demographic effectively. While there may be a correlation between political beliefs and the media accounts followed on X (for example, conservative users tend to follow conservative newspapers), the accounts operated by the Japanese-language editions of foreign media may be positioned outside these partisan alignments. Consequently, these outlets may be capable of issuing messages less likely to be filtered through ideological biases. It is inferred that encouraging such outlets to disseminate counter-narratives that inspire reflection and awareness among moderate voters could be a potentially effective approach.[19]

The content of such contributed counter-narratives should avoid political or partisan commentary. Instead, the contributions should appeal to emotion by highlighting how disinformation undermines fair elections and carries the risk of social fragmentation. As an example, this paper presents the following counter-narrative designed for moderate swing voters.

The following counter-narrative has been created for centrist audiences, focusing on evoking personal emotions. It incorporates region-specific expressions such as “naichi (内地)” meaning the mainland, which is familiar in Okinawa. It emphasizes individual experiences devoid of political partisanship, making it more accessible to middle-ground voters:

Have you ever experienced the sadness of losing touch with a childhood friend after they moved to the naichi for school? It is unfortunate when division prevents us from maintaining those bonds. Just as Operation Tomodachi strengthened ties between Japan and the US after the Great East Japan Earthquake, we too can preserve our connections in this election, even while holding diverse opinions.

This narrative focuses on the emotional impact on the individual. The use of non-partisan, individual-level content and Okinawa-specific idioms such as “naichi” or “mainland” make the narrative more palatable to moderate voters. The use of earthquake disasters, familiar to many people, refers to the risk of division. It is expected to create space for reflection and awareness on the issue of disinformation.

Next, for a broader conservative audience across Japan, this paper proposes the following counter-narrative within a national security context:

A lack of an environment where different sides can stay connected and cooperate on defense is dangerous. Just as isolated villages were left without relief supplies after earthquakes, social rifts can leave the Japanese people stressed, turning against each other. Instead of uniting to confront true threats, we may each face the enemy alone and in isolation.

This narrative emphasizes the international risks amid the spread of disinformation by domestic actors and the exacerbated polarization, which foreign actors may exploit. Since this narrative is intended for a nationwide conservative audience beyond Okinawa, it deliberately avoids election-specific terminology or partisan language that might directly provoke voters in Okinawa. Like the personal narrative, it draws on a commonly relatable theme, earthquakes, to underscore the need to protect national unity and territory. The emotional resonance is expected to leave a lasting impression.

This paper proposes inviting external contributors to craft op-eds to facilitate the dissemination of these narratives in the Japanese-language editions of international media outlets. These pieces should focus on global cases of political polarization rather than foregrounding the Okinawa gubernatorial election. Once written, the pieces could then be submitted as opinion articles. If the topic selected is timely and resonates with current public interest, the likelihood of gaining attention would increase.

By releasing these two distinct counter-narratives separately, even within the echo chambers that form around disinformation-spreading communities on X, it may be possible to bridge ideological divides between conservatives and liberals to some extent. Moreover, such an approach may shape public discourse that reaches and influences moderate voters.

6. Conclusion

This paper has examined counter-narratives in response to disinformation surrounding the Okinawa gubernatorial election, focusing specifically on dissemination through the Japanese-language editions of international media outlets. This study does not analyze the follower demographics or patterns of content diffusion on the X accounts of such outlets. Further research is necessary. Further discussion is needed on the specific procedures for providing op-eds to the press. The background of Japan, which has developed its own public relations system, such as press clubs, in contrast to Europe and the US, should be fully considered.

Today, as X itself continues to be updated daily in terms of specifications, and as technologies such as generative AI become more accessible, there may be countless types of disinformation spreading on social media and countless ways to counter it. Hopefully, research on counter-narratives will continue to accumulate, even leading to rethinking the media system.

【English Translation】

NAKAJIMA Takahiro (Master’s student, Graduate School of Law, Hitotsubashi University)

[1] Disinformation refers to the conscious dissemination of false or manipulated information with the intent of causing harm or gaining benefit. [2] Ryukyu Shimpo, “Rensai, ‘Okinawa feiku wo ou’ fakutochekku shuzaihan zadankai [Series “chasing Okinawa fake news” roundtable discussion with the fact-checking team],” Ryukyu Shimpo (September 18, 2020). (https://ryukyushimpo.jp/news/entry-864945.html Accessed on 2025-5-13) [3] Raphael S. Cohen, Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, Joe Cheravitch, Alyssa Demus, Scott W. Harold, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Jenny Jun, Michael Schwille, Elina Treyger, and Nathan Vest, “Combating Foreign Disinformation on Social Media: Study Overview and Conclusions,” RAND Corporation (July 19, 2021). (https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4373z1.html Accessed on 2025-5-13) [4] Kawashima Shin, “China’s Okinawa Policy Attracts Attention. A potential new trigger in China-Japan relations emerges,” The Diplomat (July 20, 2023). (https://thediplomat.com/2023/07/chinas-okinawa-policy-attracts-attention/ Accessed on 2025-5-13) [5] NHK aired a special program that featured this case. While a summary article of the program was initially available during the writing process, it was no longer accessible as of April 9, 2025. Information about the program can be found at the following link: NHK, “Feiku basuta-zu: senkyo to feiku [Fake Busters: ‘Elections and Fakes’],” NHK (January 20, 2021). (https://www.nhk.or.jp/archives/chronicle/detail/?crnid=A202101200119001302100 Accessed on 2025-5-13) [6] Asahi Shimbum, “Okinawa chiji no hochu, nicchu de kanshin, shu shi no ‘ryukyu tono hukai koryu’ hatsugen wo ki ni [Okinawa Governor’s Visit to China Draws Attention in Both Japan and China — Sparked by Xi Jinping’s Remark on ‘Deep Exchanges with the Ryukyu Kingdom’]” Asahi Shimbum (January 20, 2021). (https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASR7476YYR74UHBI01K.html Accessed on 2025-5-13) [7] Ryukyu Shimpo, “Tamaki chiji no kashashi douga ni netto chusho aitsugu, pekinkenjinkai tono koryukai de gakuseira gekirei “‘toshin doi’ shiranai noka?” to yogo no koe mo [Governor Tamaki Faces Online Abuse Over Kachāshī Dance Video — Encourages Students at Exchange Event with Beijing Okinawa Association, While Some Defend Him: “Don’t You Know ‘Tōshin Dōi’?”]” (July 11, 2023). (https://ryukyushimpo.jp/news/entry-1744948.html Accessed on 2025-5-13) [8] Paul Charon and Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, “Chinese Influence Operations: A Machiavellian Moment,” Report by the Institute for Strategic Research (IRSEM), Paris, Ministry for the Armed Forces (2021), p. 402. (https://www.irsem.fr/report.html Accessed on 2025-5-13) [9] One such example is the following tweet: @CYXuAXfGlfFzZCT, “#琉球新報 某海外留学経験のある高IQインフルエンサー様からお手紙♪〈仏軍報告書では明確に『この目的を中国は後押ししている』と書いており、「この目的」の説明として玉城デニーの当選を例に挙げています〉「目的」とは中国共産党の「沖縄独立計画」の事。” Post on August 31, 2022, at 14:52. (https://twitter.com/CYXuAXfGlfFzZCT/status/1564853559786557440?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1564853559786557440%7Ctwgr%5E640f330f12a424986bd039fcfdfa1fc8e740f676%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=http%3A%2F%2Falic152.blog123.fc2.com%2Fblog-entry-2781.html Accessed on 2024-3-14) [10] Kazuki Ichida, “Challenges in Measures against Digital Influence Operations: Why can’t the EU/US deal with the methods used by China, Russia, and Iran?” GGR Issue Briefing No. 63 (April 15, 2024). (https://ggr.hias.hit-u.ac.jp/en/2024/04/15/issues-in-countermeasures-against-digital-influence-operations/ Accessed on 2025-5-13) [11] Julian Richards, employing critical discourse analysis, acknowledges the inherent subjectivity and potential arbitrariness in interpretation. Nonetheless, he focuses on three key elements in his analysis of propaganda: anxiety, influence, and establishing narratives of hope and redemption. Julian Richards, “The Use of Discourse Analysis in Propaganda Detection and Understanding,” in Rubén Arcos, Irena Chiru, and Cristina Ivan, eds., Routledge Handbook of Disinformation and National Security (Routledge, 2023), p. 390. [12] For the persona analysis, reference was made to Doublethink Lab’s “How to Build a Counter-narrative?”. Doublethink Lab, “Call to Action for NGOs: Counter-narrative Development — How to Build a Counter-narrative?” (https://fight-dis.info/How-to-Build-a-Counter-narratives.html Accessed on 2025-5-13) [13] It should also be noted that there is a possibility of foreign actors exploiting such individuals. [14] It is not clear whether this article provides an accurate analysis due to the method of data collection. Unlike analyses based on data obtained via an API, this approach has limitations in terms of statistical significance. The author analyzed the account names, account IDs, and profile descriptions of approximately 80 reposting accounts that were visible on screen, using the free software tool User Local Text Mining Tool. The number of displayed words was set to 50, and parts of speech included nouns, verbs, adjectives, and others. Word size was determined based on frequency of occurrence. [15] The author analyzed the account names, account IDs, and profile descriptions of approximately 80 reposting accounts that were visible on screen, using the free software tool User Local Text Mining Tool. The number of displayed words was set to 50, and parts of speech included nouns, verbs, adjectives, and others. Word size was determined based on frequency of occurrence. [16] In the study by Nguyen et al., cases were identified in which recommender systems contributed to content diversity, going beyond the limitations of the so-called filter bubble. Tien T. Nguyen, Pik-Mai Hui, F. Maxwell Harper, Loren Terveen, and Joseph A. Konstan, “Exploring the Filter Bubble: The Effect of Using Recommender Systems on Content Diversity,” Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on World Wide Web, (2014), pp. 677-686. [17] X Marketing, “Shiten: shakaijin to tuitta [Perspective: Working Adult and Twitter]” (May 20, 2022). (https://marketing.twitter.com/ja/insights/business-people-on-twitter Accessed on 2025-5-13) [18] For counter-narratives, reference was made to Doublethink Lab’s “How to Build a Counter-narrative?” as well as the persona analysis. [19] A recent report by BBC News Japan provides an objective analysis while explicitly addressing issues such as data opacity, using phrases like “polls can be wrong.” BBC News Japan, “Igirisu sosenkyo 2024: kakuto no sijiritsu ha? Saishin no seronchosa wo kaiketsu [UK General Election 2024: What Are the Parties’ Approval Ratings? Explaining the Latest Polls]” YouTube video by BBC News Japan, June 28, 2024. (https://youtu.be/22En_4Fhw64?feature=shared Accessed on 2025-5-13)

Moriyama works for an international consulting firm, assisting a range of global companies in Japan, including those in the tech and defense industries, with their public policy and public relations activities. In addition to his full-time work, he is researching disinformation from the perspective of state-firm relations and media.