The Present and Future of Displaced Ukrainians: Rethinking Refugee Policies in Japan

Yujin Woo

(Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Law & Faculty of Law, Hitotsubashi University)

April 6, 2023

Introduction

In 2022, immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Japanese government announced that it would accept Ukrainians seeking refuge from the war. The Kishida Cabinet also provided an aid package worth 600 million US dollars and arranged transportation to bring displaced Ukrainians to Japan. As of February 2023, Japan has accommodated more than 2,000 Ukrainian displaced persons. Considering Japan’s reputation as a country that is closed to refugees, this welcoming attitude toward Ukrainians is unprecedented. The United Nations (UN) chief for refugee affairs even praised the move and asked Japan to continue its enthusiasm. However, current policies designed for Ukrainians face various criticisms and obstacles in multiple dimensions, igniting debates over what the Japanese refugee system ought to be. This briefing reviews problems associated with Japan’s handling of displaced Ukrainians as well as refugees in general. More specifically, it highlights Japan’s long-term assimilationist approach toward migrants as a critical factor that may hinder the displaced Ukrainians’ smooth and successful integration into Japanese society.

Problems with Japan’s refugee system

Japan has made an exception to its normally restrictive refugee policy by accepting a sizable number of Ukrainians, contributing to the international efforts to accommodate a large number of displaced persons from Ukraine. For these Ukrainians in Japan, the Japanese central government primarily provides visas and work permits while local governments provide food, housing, and living allowances. Despite the cooperative efforts by both the central and local governments, one of the critical concerns rests on how these Ukrainians are categorized differently from other refugees. The Ukrainian refugees are granted temporary permission to residency and labeled as “evacuees (hinanmin)” rather than refugees (nanmin). One implication of this labeling is that these Ukrainians are not recognized as official refugees or asylum seekers. In other words, there is no law with specific provisions on the duration or rights of evacuees, particularly in the long run. More importantly, they are not subject to international legal protections such as the non-refoulment clause, under which no individual can be returned to a home country if they face the risk of persecution. This temporary visa, although now renewable, was initially established based on the Japanese government’s expectation that these Ukrainians would eventually return to their country. However, the reality is that the war between Russia and Ukraine may be more prolonged than initially expected, while post-conflict recovery allowing displaced citizens and residents to safely return home will take even longer.

Furthermore, Japan’s relatively generous handling of the displaced Ukrainians has also led to criticisms from both international institutions and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Japan has received refugee applications for displaced persons fleeing from other parts of the world such as Afghanistan, Myanmar, Syria, and Vietnam. However, it often takes several years for these displaced persons to obtain the residency and work permits to which the Ukrainians are immediately entitled. Thus, Japan has been criticized for its “double standards” in dealing with Ukrainians versus other asylum-seekers. Many critics see Japan’s enthusiasm toward Ukrainians as based on political and diplomatic calculations vis-à-vis its international and regional positions.

Traditionally, Japan has been accepting a very limited number of refugees. Its average annual recognition rate has constantly been below 1% of the total number of applications throughout the postwar era. The refugee application procedure in Japan is also widely recognized to be restrictive. Because there is no concrete universal definition, Japan imposes a very strict interpretation of what constitutes a “threat.” Asylum-seeking applicants need to present documentation proving that they face the threat of persecution in their home country, including written testimony from witnesses, all of which could be impossible to gather under their given circumstances. The application forms are written in Japanese, which poses an additional barrier since they first need to develop their Japanese language skills. Consequently, many applicants fail to be recognized as refugees and are instead treated as economic migrants and held in detention centers until the government has made a decision, which can take several years. Even if they are permitted to leave the detention centers, they are prohibited from economic activities under their pending status, and hence face tremendous difficulties.

Japan’s assimilationist integration system

Although problems associated with Japan’s treatment of the displaced Ukrainians are based on specific situational and political circumstances, they mirror issues related to Japan’s attitude toward migrants in general. In dealing with foreigners, the Japanese government’s focus has fixated on maintaining the cultural status quo of the country. This norm has led to migration policies that frame migrants as sojourners instead of permanent members of society. As a result, there has been a lack of political discussion addressing the protections or rights that migrants need or deserve. Instead, the country’s migrant integration system has consequently followed an assimilationist approach. Therefore, the main concern is how to minimize the “unexpected” changes that migrants may bring to society, by forcing them to adopt Japanese norms and rules.

Indeed, Japan’s assimilationist stance toward migrants is reflected in various cross-national data. For instance, the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) measures integration policies and related rules across six continents based on various dimensions, ranging from labor market mobility to access to welfare services and legal rights such as education, health care, permanent residency, and nationality. The latest index from 2019 shows that Japan scored 47 points on a 100-point scale. This is low relative to other advanced countries; for example, traditional destination countries such as Canada, New Zealand, and the United States averaged a score of 75. Japan has continuously received low scores particularly due to the absence of anti-discrimination laws and obstacles to educational access and political participation. In fact, Japan is the only country without anti-discrimination laws among the MIPEX’s sample countries. The education system is heavily geared toward “Japanization,” with less support for education for racially, ethnically, or linguistically different groups. Since non-citizens are not entitled to any political rights, migrants cannot politically voice their concerns until they naturalize and obtain Japanese citizenship.

Another cross-national data set that allows for the assessment of Japan’s integration system is the Multiculturalism Policy Index (MCP). Simply put, multiculturalism is about recognizing and valuing group differences and respecting diverse groups maintaining their cultures and traditions. Therefore, it can be understood as the opposite of assimilation, which expects minorities to adopt majority rules and norms. Advocates of multiculturalism claim that recognition of and respect for group differences is what fosters public tolerance and acceptance of diversity, leading to healthy intercultural relations. The MCP exclusively measures multicultural policies across 21 advanced democracies. The latest index from 2020 rated Japan’s multicultural policy as 0 points on an 8-point scale. In comparison, Australia, Canada, and the United States averaged a score of 6.17. This divergence can be traced to the fact that Japan does not foster multiculturalism in education (e.g., no school curriculum, no financial support for bilingual education), in the media (e.g., no inclusion of ethnic representation or awareness of sensitivity), in social grounds (e.g., no considerations for religious practices or clothing, no financial support for ethnic group organizations), or in legal institutions (e.g., no dual citizenship, no affirmative action).

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications introduced its version of multiculturalism (tabunkakyōsei: multicultural coexistence plan) in 2006. However, the MCP notes that, despite the emergence of a multiculturalism discourse in Japan, much of it assumes that the mere existence of some degree of social diversity in itself constitutes multiculturalism. However, mere coexistence or cohabitation with migrants does not produce social acceptance of them as legitimate members of the country unless the society recognizes their distinctive circumstances and norms and becomes willing to accommodate them.

Among the many reasons underlying this persistence of assimilationism and the slow adoption of multiculturalism, some critical causes are related to the decentralized structures of both the integration system and NGOs. While the Immigration Bureau within the Ministry of Justice controls migrants’ entries and fundamental rights, the Japanese government delegates the actual responsibilities of design and implementation of integration programs to the local level. This bottom-up approach has merit in that local governments may be more aware of the specific needs of migrants residing in their areas; however, local governments have reached their financial limits in trying to deal with special accommodations some groups may require. Meanwhile, despite being rich in history and number, NGOs in Japan tend to have relatively weak political or social voices. This weakness is due to institutional challenges, such as the government’s preferential treatment of small local associations rather than large and organized ones, and strict bureaucratic regulations.

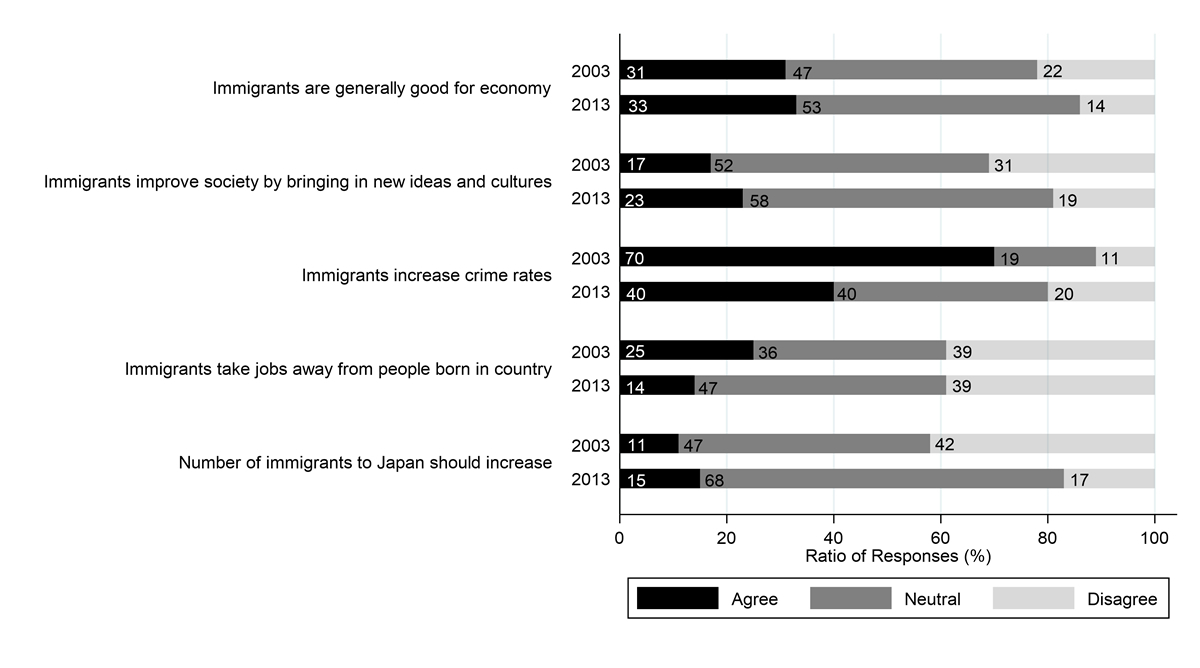

In a nutshell, the Japanese government promotes support and accommodation of migrants at the local level through decentralized coordination between local governments, civil society organizations, and foreign residents themselves. However, the government’s assimilationist attitude does not have tangible guidelines or assistance at the local level. Therefore, it seems to impede public awareness of the realities and needs of migrants, exacerbating segregation between majority and minority groups. Fortunately, the Japanese public is becoming more open toward migrants over time. For example, the National Identity surveys conducted by the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) asked identical questions related to public opinion on migration in 2003 and 2013. Figure 1 compares the answers among Japanese respondents from both years. Overall, public opinion toward migrants has become more favorable over ten years. Additionally, various polls recently taken by newspapers and NGOs have shown that most Japanese people side with the statement that the Japanese government should accept more refugees from Ukraine. It seems that this positive trend of viewing migrants among the Japanese public will continue.

Figure 1. Changes in Japanese Responses to Immigration (ISSP Data)

Note: “Agree” includes both “agree strongly” and “somewhat agree” answers. “Disagree” combines both “disagree strongly” and “somewhat disagree.” “Neutral” category also incorporates responses such as “don’t know,” “can’t choose,” and “remain the same.”

(N = 1,102 in 2003, 1,225 in 2013; only including those who self-identified as Japanese citizens).

In the Japanese survey, the term teijū gaikokujin is used. Its accurate translation is “foreigners who entered Japan under a purpose to reside.”

The path forward

Considering Japan’s current admission and integration policies, what the aforementioned evidence implies is that issues revolving around Ukrainian evacuees pose future challenges in two interlinked directions: the situation of Ukrainians themselves and anti-migration sentiment among the public. As the Ukrainians stay in Japan for a longer duration than initially expected, their needs change from those related to short-term survival to long-term, sustainable solutions such as access to education and employment. In addition to unemployment due to issues such as health, information access, linguistic, or psychological difficulties, those who do succeed in finding jobs also suffer from under-employment. Many displaced persons work part-time doing manual labor and experience distress at their inability to pursue their original career. Currently, much NGO and public support for the displaced Ukrainians exists at the grassroots level, ranging from providing essential amenities to offering Japanese language classes. Universities in Japan have also stepped forward to accept Ukrainians as students, providing them with on-campus housing and bilingual education. However, unless the Japanese government shifts its perception and begins to view foreigners as long-term members of society, policies and programs related to migrant rights and incorporation into society will continue to be limited, and essential problems facing the Ukrainians living in Japan may be overlooked.

Furthermore, the current assimilationist system may decrease public support for refugees and even ignite anti-migration sentiment. For the moment, the Japanese public has shown an unprecedented level of interest and support for the Ukrainians. According to various polls taken by newspapers and NGOs, most Japanese people support the statement “Japanese government should accept more refugees from Ukraine.” Despite this humanitarian and optimistic trend, the Japanese do not have enough experience with recognizing and living with a sizable group of refugees with cultural or ethnic differences. In this sense, the prolonged stay of the displaced Ukrainians may reinforce boundaries between majority and minority groups, causing the Japanese to bolster their national identity based on ethno-culturalism. Assuming that the number of migrants will increase, what matters is Japan’s stance on the mode of integration. This will impact the migrant experience, including interpersonal contacts between the Japanese people and displaced persons, particularly in the long run.

Reference list

ISSP Research Group. 2012. International Social Survey Program: National Identity II-ISSP 2003. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA2910 Data file Version 2.1.0.

ISSP Research Group. 2015. International Social Survey Program: National Identity III-ISSP 2013. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5950 Data file Version 2.0.0.

Multiculturalism Policy Index. 2022. Access: http://www.queensu.ca/mcp/.

Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX). 2020. Access: https://www.mipex.eu/.

Yujin Woo is an Assistant Professor at the Graduate School of Law and the Faculty of Law at Hitotsubashi University. Until 2021, Professor Woo worked at Tohoku University as a Research Assistant. She was also a Researcher at the School of Economics and Political Science at Waseda University. Before arriving in Japan, she also conducted research at Stanford University’s Asia-Pacific Research Center. Professor Woo obtained her doctoral degree from the University of Virginia and her master’s degree from New York University and Seoul National University. He completed her undergraduate degree at Smith College.